By 1965, the coin-operated amusement industry was running out of steam. In 1954, the United States Census Bureau estimated the average revenue generated by amusement machines on location in the United States at $722 per machine. By 1963, the Census Bureau estimated that the average revenue per machine had fallen to $639 despite nearly a decade of inflation and the widespread adoption of dime play. No major new product categories had emerged since the spread of shuffle alleys, bumper pool, Dale guns, and two-player pinball in the mid-1950s, while the combination of dwindling markets and consolidation had whittled down the number of manufacturers in Chicago to just five. Furthermore, the inability of operators to recoup the cost of newer machines set to dime play and the resistance of the general public to a higher cost per play had forced the manufacturers to often sell their machines at a loss, resulting in drastic cutbacks to R&D. While Midway continued to explore avenues to enhancing its novelty pieces and Williams continued to innovate in pinball, most new machines coming out of Chicago were basically identical to the machines that had come out the year before save maybe a small new gameplay feature or a new theme in the cabinet art or backglass. An increasing interest in pinball in Europe, particularly after France legalized the game in 1961, helped sustain sales for the surviving manufacturers, but without new game concepts, the long-term future of the industry began to look grim.

But once again coin-operated amusements did not die. Across the Pacific, a newly resurgent Japan, riding the wave of an economic miracle, discovered coin-operated amusements and fell instantly in love. At first merely importers of American products, in the mid 1960s local firms slowly turned to designing their own machines. Bigger, flashier, and more expensive than the arcade pieces coming out of Chicago, the leading Japanese cabinets inspired a wave of technological innovation in the coin-operated games industry that breathed new life into the moribund American manufacturers. And in this rejuvenated arcade climate, in which distributors and operators were newly aware of the potential of advanced displays, unique control schemes, and sophisticated sound, the commercial video game was born.

This is the final post in a six-part series briefly chronicling the coin-operated amusement business from its origins in 1870 to just before the introduction of the first coin-operated video game. Principle sources for this post include The Ultimate History of Video Games by Steven Kent, Winning Pachinko: The Game of Japanese Pinball by Eric Sedensky, Arcade Mania: The Turbo-Charged World of Japan’s Game Centers by Brian Ashcraft, the dissertation Game Centers: A Historical and Cultural Analysis of Japan’s Video Amusement Establishments by Eric Eickhorst, the article “Entertainment Empire of the Rising Sun: A Conversation With Sega Founder David Rosen” by Steven Kent, the article “Firm Seeks Right Button for a 2d Space Invaders” in the November 29, 1981, edition of the Chicago Tribune, the article “Lots O’Fun” in the January 15-22, 1982, issue of Event, numerous articles in Billboard Magazine, the court case Bromley v. Commissioner, 23 T.C.M. 1936 (1964), Report No. 92-418 of the United States Senate, “Fraud and Corruption in Management of Military Club Systems” (1971), a series of Twitter posts from the official account of Taito detailing the early history of the company, an obituary for Michael Kogan printed in the March 1984 issue of Replay Magazine, an interview with Masaya Nakamura in the January 1977 issue of Play Meter magazine, the article “Pac-Man creator bites into County Hall” in the August 31, 1997, edition of the Sunday Times, the 1985 article “Namco: Maker of the Video Age” in the Journal of Japanese Trade & Industry, interviews with several Kasco employees translated under the title “Kasco and the Electro-Mechanical Golden Age” and hosted at shmuplations.com, and the blog All In Color For a Quarter maintained by Keith Smith.

The Birth of Coin-Op in Japan

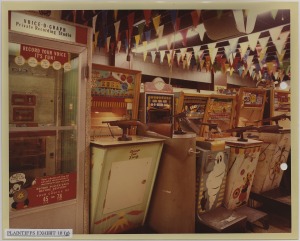

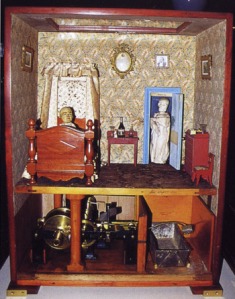

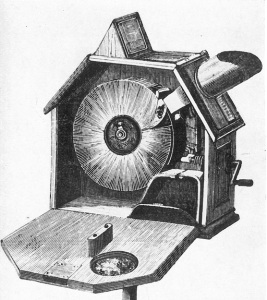

The Masamura ALL-15, which helped revolutionize pachinko

The emergence of a coin-operated industry in Japan was a slow process complicated by the depletion of Japanese industry as a result of World War II. Before the war, Japan had just begun taking its first steps in the field through a unique game called pachinko. Like pinball, pachinko evolved out of bagatelle, which first reached Japan around 1924, perhaps through a child’s toy version of the game imported from the United States called the Corinth Game. The game soon became common in candy stores across Japan, with children able to win candy or pieces of fruit for high scores, and gained the name “Pachi-Pachi” after the onomatopoeia describing the clicking of small objects such as the balls in the game. Before long, the game spread to markets as well, where adults would play for the chance to win prizes such as soap or cigarettes. The narrow tents and stalls in Japanese markets were not well suited to bagatelle tables, so by 1926 operators were introducing vertically oriented cabinets to reduce their footprint, perhaps taking inspiration from the allwin games popular in Europe. These gambling devices, pioneered in 1900 in Germany with the Heureka, call on the player to press a lever to launch a small ball onto a circular track in the hopes that it will land in a scoring hole so he may win a prize. The vertical orientation, spring-loaded lever, and circular track of the allwin were all features incorporated into the modified bagatelle game the Japanese were now calling pachinko, a combination of the aforementioned “pachi” and “ko,” the Japanese word for ball. As the new game grew in popularity, Japan’s first dedicated pachinko parlor opened in Nagoya in 1930, but just as the game appeared ready to hit a rapid growth phase, the government halted production of all machines in 1937 due to Japan’s need for resources to support its war with China. In 1938, the government went a step further and ordered the closure of all the pachinko parlors in the nation. They would remain closed for the duration of what quickly spiraled into World War II.

In 1946, pachinko returned to Nagoya and from there began spreading across the country once more, but the game did not really take off until a series of important innovations by Shoichi Masamura. Like the earliest pinball games, pachinko before and immediately after World War II was a relatively static game in which the player launched a ball that moved through a nest of pins and perhaps entered a scoring hole. In 1948, Masamura introduced spinners and additional pins on his machines to create a layout known as the “Positive Gage Forest,” allowing balls to bounce around the playfield and creating additional opportunities for them to land in a scoring hole. In the mid 1930s, pachinko manufacturers had developed a form of score keeping in which the machine would automatically eject a ball whenever the player successfully scored, which could be exchanged for a prize. In 1949, Masamura took this concept a step further with the introduction of the ALL-10, which paid out ten balls instead of one. The next year, he upped the total to fifteen in his ALL-15 machine to establish a standard that lasted for three decades.

The impact of pachinko on post-war Japan was unlike any coin-operated machine phenomenon the world had seen to that point. By playing the game, Japanese citizens were able to win everything from soap to vegetables to cigarettes, all of which were in incredibly short supply after World War II. Therefore, the number of pachinko parlors in the country expanded rapidly to a peak of 70,000 in 1953 housing over two million machines taking in over $42 million per month, more than all the department stores in Japan combined. After the government began regulating the industry more closely in 1954, the number of parlors dropped rapidly to a low of 8,000 housing half a million machines in 1956. The introduction of lighting and electrically powered “tulip” scoring pockets in 1960 helped revive interest in the game again, which continued to grow steadily in popularity over the next two decades.

While profitable in the early 1950s, the pachinko industry had more in common with America’s coin-operated gambling business than with its amusement business and did not represent a wider adoption of coin-operated equipment in Japan. Before World War II coin-operated amusements were just beginning to penetrate the country in the early 1930s as the first dedicated game centers began to appear. The pioneer in this field was Kaichi Endo, a purveyor of automatic signs, vending machines, and rocking horses. In 1931, Endo approached the Matsuya department store in Asakusa with a plan to create an amusement venue on the roof of the store combining activities like roller skating, archery, and cycling, with equipment like rocking horses, coin-operated testers, and peep shows. Endo dubbed his new entertainment venue “Sports Land.” Sports Land proved successful, and before long most of Japan’s major department stores incorporated rooftop amusement spaces into their business.

World War II signaled the end of Japan’s first coin-operated amusement industry. While a small number of refurbished arcade machines entered the local economy in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Japanese people were still desperately trying to recover from the complete devastation of the War and had neither the free time nor the disposable income to engage in most leisure activities. At the same time, however, the United States military began significantly increasing its presence in the country due to the outbreak of hostilities in Korea. This attracted several businessmen interested in providing entertainment for the American servicemen in the country, including influential American distributor Irving Bromberg.

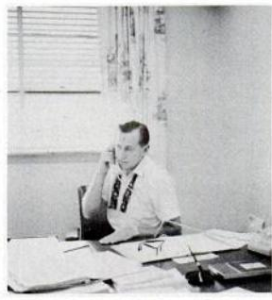

Marty Bromley (l) and Irving Bromberg, who built a vast coin-op empire under the name Service Games

Born in 1899 to Russian Jewish immigrants like so many of the early pinball magnates, Bromberg worked as a glass salesman as a young man and then served as president of the Greenpoint Motor Car Corp. in Brooklyn from 1923 to 1930 before leaving to establish a vending machine distributor called the Irving Bromberg Company. When Leo Berman decided to sell the early pingame Bingo nationally, he traveled to New York to interest Bromberg in selling the game in the city. At the time, Bromberg had no storefront of his own, so he contacted his friend Hymie Budin, who sold items for vending machines, and got permission to display Bingo in his storefront. After some initial difficulty generating interest in the game, Bromberg caught the attention of Bill Shorke, one of the last great penny arcade moguls from the turn of the century, and sales took off. In 1932, Bromberg became a distributor for Bally pins, which helped him grow to become one of the largest distributors on the East Coast and open branch offices in New York City, Boston, and Washington, D.C. Around March 1933, Bromberg moved to Los Angeles to become the first Bally distributor on the West Coast, and he must have enjoyed his new home, because in July he sold his New York and Brooklyn offices (and probably his Boston and Washington operations as well) to focus on the Los Angeles market. He retained ties with New York, however, which became vitally important when Harry Williams developed Contact. Bromberg provided the first national distribution for the game by shipping tables into the New York area, thus playing a critical role in the spread of this highly influential pin game. Bromberg continued to run his company in Los Angeles until he sold out to another distributor in 1946, possibly because he was becoming more involved in a new venture set up in partnership with his son, Marty.

Martin Jerome Bromberg was born in 1919 and operated his first coin-op machines while still a student before entering the family business after graduating high school. In 1940, Marty, who later changed his last name to Bromley, expanded the business by forming a partnership called Standard Games in Honolulu, Hawaii, with his father and friends Glen Hensen and James Humpert to operate slot machines and other coin-operated equipment on American military bases in the territory. Inducted into the Navy after the outbreak of World War II, Bromley worked at a Pearl Harbor shipyard so he could be placed on the inactive duty list and continue to run the Standard Games operation through the end of the war. In 1945, Bromley and Bromberg sold off Standard Games, after which they joined with Humpert to establish a new company in Honolulu to continue their coin-op business called Service Games.

In 1951, Service Games faced a serious threat to its business activities with the passage of the Johnson Act, which not only limited the sale of coin-operated gambling devices, but also banned their operation on military bases within the United States. Stuck with a stock of suddenly worthless slot machines, Bromberg and Bromley decided to send a company salesman named Richard Stewart and a company mechanic named Raymond Lemaire to Japan to establish a company that would buy the equipment from Service Games and operate it at American military bases in the country, which were not subject to the ban. The duo established a partnership called Lemaire & Stewart for this purpose in May 1952. When this business proved successful, Stewart, Lemaire, Bromley, Bromberg, and Humpert formed a new Service Games company in September 1953 as a Panamanian Corporation with Irving Bromberg as president and Dick Stewart as general manager with the sole purpose of purchasing coin-operated equipment from Chicago firms like Gottlieb, Bally, and United and shipping it to Lemaire and Stewart’s partnership, now incorporated as Japan Service Games, so they could operate the machines in the officers’ clubs and open messes of U.S. military bases not just in Japan, but also in Korea, the Philippines, and Guam. The original Service Games in Hawaii also remained a going concern until the Brombergs sold it in 1961.

In 1953, a second company followed Service Games into the Far Eastern military base market, the Cosdel Amusement Machine Company founded by a former U.S. Navy pilot named Kenneth Cole who chose to settle in Japan after the War, which became a distributor of coin-operated amusements and Wurlitzer jukeboxes to bases not only in Japan, but also in Okinawa, Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong before ultimately shifting its focus to the record business. As companies like Service Games and Cosdel brought an increasing amount of coin-operated equipment into Asia, a new Japanese coin-operated industry began to take hold as machines originally intended for U.S. military bases began migrating into the local economy through the work of entrepreneurs like Russian businessman Mike Kogan.

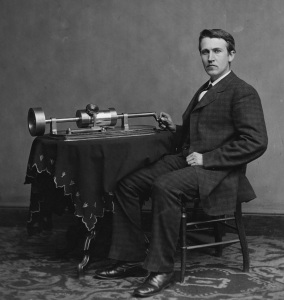

Mike Kogan, the founder of the Taito Trading Company

Born into a Jewish family in Odessa, Ukraine, in January 1920, Michael Kogan fled with the rest of his family to Harbin, Manchuria, soon after to escape the Russian Civil War. When Japan occupied the region in 1931, Kogan and other Jewish refugees endured anti-Semitism from Japanese soldiers, but they were also afforded unique opportunities after a small group of military leaders led by Norihiro Yasue bought into anti-Semitic conspiracy literature describing Jewish control of world finance and media and believed Japan should harness the expertise of Jewish refugees in Manchuria to further develop Japan. While Yasue ultimately never realized his so-called Fugu Plan, the brief pro-Jewish sentiment his ideas generated gave Kogan the opportunity to study economics at the prestigious Waseda University beginning in 1939. The outbreak of World War II stranded Kogan in Japan, but in 1944 he was finally able to get out of the country and join his father in Shanghai. Once there, he founded a trading company that operated under the name Taitung –which translates to “Far East” in English and “Taito” in Japanese — specializing in floor coverings, hog bristles, and natural hair wigs. Kogan relocated to Tianjin in 1946, and then to Tokyo in 1950 after the communist takeover of China. Kogan was forced to liquidate his business in the move, but he established a new trading company in 1950 called Taito Yoko. When that business failed, Kogan established the Taito Trading Company in 1953. At Taito, Kogan distilled the first vodka ever produced in Japan and took his first steps into the coin-op industry by importing and distributing a popular line of peanut vending machines and a less successful line of perfume machines.

In 1954, Kogan led Taito into the jukebox business. Unable to secure a license to import machines from the United States because they were classified as luxury items by the Ministry of Industry and Trade, Kogan instead turned to U.S. military bases to purchase broken-down used machines and salvaged parts from three or four of them at a time to cobble together working units. The jukebox business was not very lucrative at first, but once Taito began mixing in traditional Japanese records with American popular music sales began to climb until there were over 1,500 jukeboxes on location in Japan by 1960. In 1956, Taito even developed the first jukebox designed and built entirely in Japan, but quickly abandoned plans for production of the model when Kogan discovered that relatively muted demand made it more economical to continue purchasing American machines. As the Japanese economy improved, Taito finally secured a deal to become the official Japanese distributor of AMI jukeboxes in 1958, ending its reliance on refurbished machines. A deal with Seeburg to become the exclusive Japanese agent for the company in 1962 further solidified its position as one of the top jukebox companies in the nation.

At the same time Taito began exposing Japan to the jukebox, an American named David Rosen began laying the groundwork for a new company that would finally bring a full-fledged coin-operated amusement industry to the country. A Korean War veteran, Rosen’s tour of duty with the United States Air Force from 1949 to 1952 took him across Asia from Shanghai to Okinawa, but he spent the majority of his service in Japan. Rosen quickly fell in love with the country and also realized there was great economic opportunity in the nation despite the complete economic collapse brought on by the war because the inhabitants were too industrious to stay down for long. As a result, Rosen took advantage of a developing trade in portrait painting by establishing a business called Rosen Enterprises in 1951 that arranged for photos in the United States to be sent to Japan to be made into portraits. Upon leaving the Air Force, Rosen returned home to New York with the intention of finishing his degree while furthering the interests of his portrait business in his native country. The business proved unsuccessful, however, so Rosen dropped out of school and returned to Japan in 1954 to transform Rosen Enterprises into a trading company that exported products like paintings, sculptures, and woodcrafts and manufactured small items like cigarette lighters and money clips for the domestic market.

At the time Rosen returned to Japan, the country was still recovering from the devastation of World War II, and every citizen required an ID card for rice rations, railway passes, school applications, and employment. Therefore, there was a brisk trade in photographs for ID cards, which usually cost 250 yen and took 2-3 days to develop. Rosen realized that he could import photomat booths from the United States that were not only cheaper, but also developed the film nearly instantaneously. After testing the photomats, however, Rosen realized that modifications would have to be made because the photos would fade within two years due to inadequate temperature controls, making them useless for official IDs. To solve this problem, Rosen modified the photomats so that a person inside the booth actually developed the film and monitored the temperature, allowing for the creation of photos that would last four to five years. Importing his first booths in early 1954, Rosen soon had a massive hit on his hands as people began waiting in line for over an hour to pay 150 yen to have a picture taken that would be developed within two minutes. Before long, Rosen’s booths, marketed under the Photorama brand name, could be found in over one hundred locations around the country. Rosen’s success soon caused a small international incident as traditional photo studios began staging protests over unfair American business practices, leading him to establish a franchise system. Rosen licensed his technology and supplied film to a group of franchisees that opened another hundred locations, but opening up his system also led to competition from other businesses that began deeply cutting into Rosen’s profits. Therefore, while Rosen kept his Photorama business going into the early 1960s, he began looking for new avenues to expand.

By 1956, the Japanese economy was showing signs of revival, and for the first time since the War Japanese citizens were beginning to have both leisure time and disposable income. Rosen therefore decided to enter the business of what the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry called luxury goods, which required an import license that until recently had been nearly impossible to acquire. Rejecting the currently popular entertainments of pachinko, dance studios, bars, and cabarets, Rosen decided to focus on coin-op games and negotiated a license to bring in $100,000 worth of merchandise and then acquired older games at a relatively cheap price from distributors in the United States who had accepted the games as trade-ins for newer product and then just piled them in warehouses with no idea what to do with them. Rosen concentrated on gun games like Seeburg’s Coon Hunt and Shoot the Bear because owning a firearm was illegal in Japan and these games gave the public an outlet for target shooting. Rosen leveraged good relations forged during his Photorama days with the Toho and Shochiku movie theater chains to place “gun corners” in their establishments. The success Rosen experienced with these first locations allowed him to negotiate a new license for another $200,000 worth of equipment the next year, setting the stage for massive growth in the Japanese coin-operated amusement sector.

Dave Rosen, the father of the Japanese coin-operated amusement business

By 1960, Rosen Enterprises had established at least one movie theater arcade in every major city in Japan, but it was Taito that ultimately took the lead in the new industry, opening Japan’s first large game center near Ureoku Station in Osaka in 1960, which contained over forty shooting games and pinball tables, and becoming the Japanese distributor for Gottlieb pinball machines in 1963. David Rosen, meanwhile, continued to look for other avenues through which to expand his business. A purchased indoor computer golf game failed because the Japanese considered golf an outdoor game, while a slot car business created only a brief fad, but Rosen experienced another success when he decided to establish a bowling alley in Japan. By this point, bowling had been popular in the United States for just over a decade and had reached American military bases in Japan by 1952, but the game had never penetrated the local economy save for a single location in Tokyo that catered to American servicemen. To change this, Rosen decided to place his alley in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo, a popular entertainment area that would guarantee high turnover, and secured space for fourteen lanes in this crowded area by approaching the president of one of the movie theater chains with which he already did business and reaching an agreement to place the alley over one of his movie theaters. Rosen’s alley ended up setting business records as the Japanese embraced bowling as a pastime.

As Rosen’s alley began to take off, the two largest U.S. bowling firms, AMF and Brunswick, partnered with Japanese firms C. Itoh and Mitsui respectively in 1961 and ultimately captured over two-thirds of the domestic bowling business between them. Consequently, bowling alley operation never became an important component of the Rosen Enterprises business. Bowling alleys did, however, become a prime venue for arcade games, so as the number of locations in the country grew into the hundreds and then into the thousands, coin-operated amusements became ubiquitous across the nation. A retail boom in the late 1960s contributed further growth to the industry. As the number of shopping malls, department stores, and supermarkets exploded in the latter half of the decade, they often agreed to host game centers adjacent to their retail spaces or in their rooftop gardens, giving the games even greater exposure.

With demand for arcade games high by the middle of the 1960s, Japanese coin-op firms turned to building their own products for the first time. Taito once again led the way by establishing a new subsidiary called Pacific Amusements Limited in 1963. Pioneering efforts by the company in the years following the establishment of Pacific included an early pachisuro machine, a type of slot machine derived from pachinko, to coincide with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and Japan’s first crane machine, the Crown 602, which became an instant hit when deployed in 1965 and inaugurated a product category that has been popular in Japanese game centers ever since. Before long, dozens of small companies were following Taito’s lead by setting up their own manufacturing operations.

The Service Games Complex

The board of directors of Sega Enterprises, Ltd. Dick Stewart is seated at the head of the table. Immediately to his left is David Rosen, and next to him is Ray Lemaire.

While Taito and Rosen Enterprises focused on the Japanese market, Marty Bromley and Irving Bromberg took steps to turn the country’s other large coin-operated amusement provider, Service Games, into an international coin-op empire. Since 1952, the father and son duo had been funneling amusement equipment into the Far East from Panama-based Service Games to Service Games of Japan. Now, they prepared to reverse this process by bringing equipment produced in Japan to the rest of the world. In 1956, a new wholly-owned subsidiary of Service Games was organized in Panama called Club Specialty Overseas, Inc. (CSOI) to serve as a financial clearinghouse for the global operation and to serve as the middle man between Service Games manufacturing and distribution operations. Then, in 1957, Service Games Nevada was incorporated to give the company a presence in the U.S. market and to serve as a final assembly point for slot machines to circumvent a law requiring that machines bought by the government had to be American made. The same year, the company bought a never-before-used Mills tooling set from Bell-O-Matic — for whom it already served as an official distributor in the Far East — and began manufacturing replacement parts and modified Mills designs in Japan. These machines were then funneled through Service Games Nevada and CSOI to Service Games Japan and Service Games Korea in the Far East and another Bromley distributor called Firm Westlee in West Germany for distribution to American military bases. Service Games marketed both its Mills-produced slots and the machines it manufactured itself under the brand name Sega, a contraction of the company name.

As the Service Games complex expanded its operations, it soon attracted intense scrutiny from both the U.S. and Japanese governments. Starting in 1954, the company continually faced accusations of smuggling, fraud, bribery, tax evasion, coercion, and intimidation in its quest to become the largest supplier of coin-operated equipment to the United States Armed Forces around the world. The charges rarely stuck, but there were consequences. In 1959, the Navy banned Service Games from all its bases in Japan, followed by a complete ban in the Philippines the next year. In 1961, the U.S. Civil Administration of Okinawa fined Service Games for smuggling, fraud, bribery, and tax evasion. In 1963, the Air Force banned Service Games from all its bases worldwide.

Perhaps due to so many government investigations tarnishing the Service Games name, Bromley reorganized his web of businesses in the early 1960s. First, on May 31, 1960, Service Games Japan was terminated and two new companies were formed to replace it. Nihon Goraku Bussan KK, literally Japanese Amusement Products Company, Inc., which also did business as Utamatic Inc., was led by Dick Stewart and managed the Service Games operating business in Japan, while Nihon Kikai Seizo KK, literally Japanese Machine Manufacturers Company, Inc., which also did business as Sega Inc., continued the Service Games manufacturing operation under Ray Lemaire. The same year, Firm Westlee changed its name to Standard Equipment & Service, while Service Games Korea became Establishment Garlan. Finally, in 1962 Service Games Panama was dissolved and superseded by CSOI, which became the new heart of the Service Games complex and expanded aggressively into Southeast Asia and England to complement its business in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and West Germany. Controversy continued to plague the company, however, culminating in a Congressional investigation in 1971 focused on activities in South Vietnam, where Service Games had cornered the coin-operated machine market in the late 1960s through an intermediary named William Crum and his company Sarl Electronics, allegedly helped by widespread bribery of military personnel.

In Japan, Nihon Goraku Bussan and Nihon Kikai Seizo played a key role in the growth of the local coin-operated machine industry. Like Taito, Nihon Goraku Bussan became a major supplier of machines for the domestic market, with a particular focus on jukeboxes. Though it did not run its own arcades, the company imported Rockola jukeboxes and amusements manufactured by Bally and Williams, while also distributing Sega machines produced by its sister company, Nihon Kikai Seizo, which now offered a diverse range of slot machines. In 1960, Nihon Goraku Bussan developed the first Japanese-designed jukebox to actually enter production, the Sega 1000, which was manufactured by Nihon Kikai Seizo. As both companies continued to flourish, they became one company again in June 1964 when Nihon Goraku Bussan absorbed Nihon Kikai Seizo. By 1965, Nihon Goraku Bussan had placed over 3,000 jukeboxes on location and opened branch offices all over Japan.

As Nihon Goraku Bussan and Taito grew in size and scope, a wave of new companies entered the market, and rival firms captured the new bowling business, David Rosen watched as his prime position in the Japanese arcade industry began to dissipate. His rivalry with Japan’s other two large coin-op enterpries always remained friendly, however, so in 1964 he proposed a merger with Nihon Goraku Bussan to create a company that could remain atop the increasingly competitive Japanese coin-op industry. On July 1, 1965, Nihon Goraku Bussan acquired Rosen Enterprises and changed its name Sega Enterprises, Ltd. Rosen became the CEO and managing director of the company, while Dick Stewart became president, and Ray Lemaire took the title director of production and planning. Under Rosen, the combined company began phasing out slot machine production and equipment sales and leasing to military bases so that it could focus on a new primary objective: becoming the top coin-operated amusement company in Japan to facilitate becoming a publicly traded corporation.

Periscope, Sega’s first international hit, adapted from a similar game created by the Nakamura Manufacturing Company

By the time, Rosen instigated the creation of Sega, he had long since moved from importing used games to bringing the latest products over to Japan, but was growing increasingly frustrated with the stagnation taking hold in Chicago. He therefore decided to take advantage of the Service Games jukebox and slot machine factory to follow the lead of Taito by manufacturing his own product. Rosen sensed he could find a niche for Sega in the mid-range novelty market, which had virtually disappeared in the United States. In 1967, Sega became the first foreign manufacturer to join the MOA and completed a deal with Williams to introduce its games in the West. Rosen’s plans changed, however, thanks to an impressive new game from one of his competitors, the Nakamura Manufacturing Company.

Born in 1925 in the Kanda District of Tokyo, Masaya Nakamura was the son of a handcrafted shotgun manufacturer who’s business was destroyed in World War II. The elder Nakamura salvaged what he could from the rubble and opened a gun repair shop in the same Matsuya Department store that had once housed the first Japanese game center on its roof. Meanwhile, Masaya attended Yokohama State University, but could not find a job in the depressed Japanese economy after graduating with a degree in shipbuilding in 1948. He therefore worked in his father’s store performing a variety of odd jobs from sweeping the floors to bicycling around the city to hang advertising posters of his own design. Over time, the Nakamuras transitioned from repairing old rifles to selling brand new air guns, but looming new restrictions on gun ownership and shooting soon threatened the business. The inventive Nakamura decided to modify the guns into children’s pop guns, which brought the family into the toy business.

With the family’s new focus on toys, Masaya Nakamura soon turned his attention to other forms of children’s entertainment. In the 1950s, rooftop amusement spaces were making a comeback in Japan, but the Matsuya store in Yokohama still did not have one. Nakamura therefore purchased two crank-operated mechanical horse rides and received permission to place them in the rooftop garden of the store. Seeing the potential for a new industry, he subsequently established the Nakamura Manufacturing Company in 1955 with just two employees and roughly $1,200 in financing to operate mechanical horse rides in rooftop amusement spaces.

The company initially operated in just a couple of locations, but in 1963 Nakamura accepted a contract to build a rooftop amusement park for the flagship location of Japan’s premiere department store chain, Mitsukoshi, located in the Nihonbashi District of Tokyo. In addition to horse rides, Nakamura added a 3D sound and picture viewing machine, a pond out of which children could scoop goldfish, and an elaborate amusement machine called the “Roadway Ride.” Based on the success of this venue, Mitsukoshi decided to add rooftop amusement parks to all its locations, and Nakamura was soon operating ten facilities across Japan.

By 1966, Nakamura had emerged as one of Japan’s premiere operators of coin-operated amusements, but faced new challenges in a changing market. As the Japanese industry rapidly expanded, manufacturers proved unable to keep up with increasing demand, while larger companies like Taito and Sega that served as both operators and manufacturers were beginning to invade Nakamura’s traditional stronghold of department store play areas. Nakamura responded by opening a new factory that year in the Ota-ku district of Tokyo and secured a license from the Walt Disney Company to use its characters on his projects. Initially, the factory just produced kiddie rides, many of which were modeled on Walt Disney characters, but Nakamura soon turned his attention to more elaborate coin-operated amusements beginning with a game called Periscope.

A target shooting game, Periscope broke new ground in the genre with a gigantic cabinet featuring a plexiglass ocean and plastic ships on a motorized carriage, great electronic sound effects, and an innovative control scheme in which up to three players peered through actual periscopes to target and destroy the ships with torpedoes represented by points of light that traveled across the fake waters. A far more expensive game than the typical $695 machine of the time, Periscope proved a hard sell at first, but the game soon became a hit when arcade operators realized that it could bring in sustained earnings far in excess of most coin-operated games.

When Dave Rosen at Sega noticed the game began drawing attention from distributors in the United States and Europe, he decided to manufacture a version of Periscope for foreign markets. After showing the game at conventions in the United States in Europe in late 1967, however, he quickly realized that it was too large and expensive for export, so he had a single-player unit designed. Still coming in at roughly $1295 when the typical arcade piece would sell for half that amount, however, distributors complained that no one would be able to make money on the game. Sega responded by advising them to sell it on quarter play. Released internationally in March 1968, the single-unit Periscope revolutionized the coin-op industry as the public proved willing to embrace quarter play for such a sophisticated entertainment experience. Too large even in its smaller form for typical street locations, Periscope nevertheless found a home in retail establishments like department stores and shopping malls that would never typically host coin-operated amusements.

With revenues increasing rapidly at Sega thanks to Periscope and the continued growth of the jukebox business — in which Sega had captured just under half of the market with 5,000 machines on location by 1967 — Rosen’s dream of going public suddenly appeared feasible. The company retained an underwriter to begin work on an initial public offering, but ultimately decided the hurdles would be too great. Not only would Sega have been the first American company to go public in Japan since World War II, but it would have also been the first coin-operated amusement company to ever go public in the nation. Rosen and his partners therefore began a search for a Western company that could help take Sega public in the United States and ended up selling to Gulf & Western in 1969, where CEO Charles Bludhorn was on a massive acquisition spree that made the company one of the largest conglomerates in the world. Between June 1969 and January 1970, Gulf & Western purchased 80% of the stock of Sega Enterprises — the entire company save Ray Lemaire’s 20% stake — for a total price of $9,977,043. Bromley and Stewart ended their direct involvement with the company at that point, while Rosen became chairman and CEO of Sega.

Realistic Games

Chicago Coin’s Speedway, perhaps the biggest coin-op amusement hit of the 1960s.

With Periscope proving a major hit despite its technical complexity and high price per play, the game spearheaded a revival of the moribund novelty game manufacturing business through a new category labelled “realistic games” in the trade press that incorporated advanced special effects to provide a closer simulation of the real world than previous arcade pieces. For example, Dale gun games began incorporating electronic sound effects to provide more realistic gunshots and explosions, while Sega produced an elaborate flight game in which the player controls a helicopter spinning on a metal arm attached to a plastic mountain that incorporates an 8-track player to provide the sound of the engine and rotor, which actually changes tempo to match the speed of the helicopter. The most important of the realistic games, however, were a new wave of driving games spearheaded by a Japanese manufacturer called Kasco.

Established in 1955 by engineer Kenzou Furukawa under the name Kansei Seiki

Seisakusho and incorporated three years later, Kasco’s first product was a magic lantern device called the “Stereo Talkie” intended to help guide shoppers around the stores of the Hankyu Department chain. As rooftop amusement spaces became popular in Japan, Furukawa repurposed the Stereo Talkie as a picture viewer amusement device called the “Viewbox” that displayed images from Japanese folktales and small comic strips, often accompanied by music. Like Nakamura Manufacturing, Kasco began installing and maintaining kiddie rides in rooftop gardens and transitioned into importing, operating, and manufacturing other types of coin-operated amusements such as a new driving game that would transform what had largely been a niche game type into the arcade’s premiere attraction.

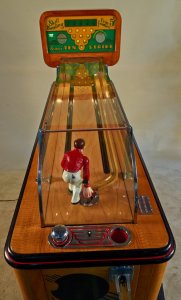

Drive Mobile (1941), the first popular coin-operated driving game in the United States

The first coin-operated driving games — like so many of the early coin-op technologies — were developed in Britain. The earliest known patent for such a game was filed in 1928 by Algernon Evans, though it appears this game was never built. In 1931, another British inventor named Mark Myers patented a game called Road Test that featured a model car set atop a metal drum with a road painted on it that would constantly shift to the left and right as it rotated. The player had to use an actual steering wheel to keep the car centered on the road. In 1941, International Mutoscope introduced the driving game to the United States with a similar concept called Drive Mobile that added a lighted backglass to keep track of the player’s progress across a map of the United States, with the player scoring more points the longer he is able to remain on the road. The concept proved popular, so Mutoscope released a two-player version called Cross Country Race in 1948 and a deluxe version with a sit-down cabinet, Drive Yourself, in 1954. Driving games became one of the staples of the 1950s and 1960s fun spot, with most either using the rotating drum method or slot cars like those found in a toy racing set. They were generally overshadowed by other arcade pieces, however, and few models were designed.

In 1969, Kasco introduced a new driving game called Indy 500. The game’s elaborate

cabinet featured a circular racetrack and several cars painted on individual rotating discs that were illuminated by a lamp, providing striking, colorful graphics and allowing the game to detect collisions between the vehicles. The player therefore not only had to keep his car on the track, but he also had to avoid the other cars to avoid a crash that brought his vehicle to a halt. Electronic sound provided both the steady hum of the car engines and the sounds of impact. Far more realistic and exhilarating than any driving game released before, it became a smash hit in Japan with sales of over 2,000 units.

With Indy 500 proving so successful, Kasco licensed the design to leading novelty game producer Chicago Coin for release in the United States. Dubbed Speedway, the game became the biggest smash hit the industry had seen in years, selling over 10,000 units. The game also played a critical role in the growth of quarter play: Chicago Coin wanted to set the machine to one play per quarter just like Sega’s Periscope, but operators initially balked and asked for two plays per quarter. Chicago Coin therefore tested the game both ways and discovered both models received roughly equal play, which meant the quarter play machine took in twice the money since a single coin bought half the playtime. Speedway consequently shipped with one play per quarter, cementing a new price point that would persist for over twenty years.

In 1969, Sega scored another major hit in the U.S. with Missile. Continuing to push state of the art graphical effects, the game features a rotating filmstrip displaying silhouettes of jet planes that is projected onto the back of the cabinet to create the illusion that waves of bombers are flying towards the player. As the planes move across the cabinet, a wiper blade travels along a circuit board containing a series of contacts. The player must shoot down the planes by aiming his missile using two buttons to rotate it left or right, then firing by pressing a button on top of a

joystick. The missile is attached to its own wiper that passes over a series of contacts, and if both the player’s missile and the wiper tied to the movement of the bombers on the filmstrip are touching the same contact when the player presses the button, a circuit is completed to register a hit and a solenoid pulls a different slide in front of the projector displaying a red explosion graphic.

By 1970, a slew of manufactures both old and new were rushing to emulate the cartoon-like graphics and realistic sound effects of Speedway and Missile, setting off a technological arms race to provide new arcade experiences unlike any the public had experienced in an arcade before. As a result, the early 1970s were perhaps the best opportunity since the Great Depression for a clever inventor with a slick new product to break into the industry despite having little working capital and/or no previous track record with coin-operated amusements. In other words, there would probably never be a better time for Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney to introduce the first video arcade game.