Pinball ruled the roost of the 1930s arcade, selling in numbers that no other coin-operated amusement could approach, but it was hardly alone. Sports games, shooting games, athletic machines, crane games, and a whole host of other exotic contraptions continued to exist alongside pin tables under the catch-all categories of “novelty amusements” or “arcade pieces.” After pinball’s decline in the 1950s due to bingo machines, gambling stigma, and the Johnson Act, many of these products came out from pinball’s shadow to take center stage in the industry. Pinball did not vanish, of course, continuing to contribute significant revenues, but it was no longer the dominant game in production. Instead, it was the novelty products that drove the industry, with new concepts like shuffle alleys and bumper pool briefly taking the market by storm and then being superseded by the next big thing. At the same time, the decline of the inner city and the rise of suburbia coupled with the onset of the Baby Boomer generation signaled a shift in arcade venues once again. While the big inner city arcades did not disappear entirely, by the end of the 1950s coin-operated amusements had dispersed across fun spots like bowling alleys and skating rinks and shopping venues like department stores and discount houses while exhibiting a new focus on children’s entertainment. This helped precipitate a period of rapid consolidation that left only five major producers of coin-operated games by 1965.

This is part four in a six part series examining the history of the arcade industry from its earliest days until the dawn of the video game era. Principle sources this time around were Automatic Pleasures by Nic Costa, Arcade 1: Illustrated Historical Guide to Arcade Machines by Richard Bueschel and Steve Gronowski, numerous articles in Billboard Magazine from the 1950s and 1960s, the website pinrepair.com. and the forthcoming book All In Color For a Quarter to be published by Keith Smith (no relation).

Bats, Balls, Pins, and Pucks

The playfield of All American Baseball, the first pitch-and-bat style coin-operated baseball game

The first novelty games to achieve prominence in the late 1920s were the floor-model sports cabinets like the Chester-Pollard football and golf games that fueled the new Sportland arcade. This genre enjoyed its peak popularity between 1927 and 1931, after which the high cost of the cabinets and the nickel playing price left an opening for the penny play pinball machines to begin their rise to dominance. Nevertheless, new sports games would continue to appear from time to time during the Depression, complimenting the pinball and crane games that dominated the decade. After World War II, with pinball on the decline and crane games banned entirely by the Johnson Act, sports games began appearing in greater numbers, although they were never one of the main selling points of the arcade. While at least one game for just about every popular sport in the U.S. was released over the next two decades, the most widely emulated sport was baseball.

The first known coin-operated baseball game was created by Californian George Miner in 1929. Both an avid baseball fan and an accomplished coin-op engineer, Miner combined his interests in the All American Baseball Game. Clearly inspired by the Chester-Pollard output, All American Baseball featured manikins displayed in a large wooden cabinet and a bat controlled by a lever similar to the one on the Play Football game. Holes in front of each fielder represented outs, while a series of troughs along the back of the cabinet represented everything from a foul ball to a home run. For a nickel, the player could keep swinging at balls until he made three outs. Miner established the Amusement Machine Corporation of America in Nevada in 1930 to sell the game, but in 1931, he sold the rights to Harry Williams when the sports game market went south. Williams remained enamored with baseball games for the rest of his career and became one of the principle drivers of the market both before and after establishing the Williams Manufacturing Company in 1943. In 1935, after he joined Bally, he and Miner prepared to create an updated version of All American Baseball for the company, but these plans were cut short when Miner died in a plane crash on October 7. When Williams moved to Rockola in 1937, however, he brought the Miner patents and tooling with him and created World Series 1937, which proved a modest hit.

After World War II, Bally ushered in a new era of baseball games in 1947 with Heavy Hitter, for which it purchased the rights from its inventor, a Royal Oak, Michigan, cab driver named Jimmy Keller. Key to the new game’s popularity was the fast, unpredictable delivery of the ball, accomplished through a mechanism that launched it from under the table. Several imitations followed from companies like Gottlieb and United, but the Williams Manufacturing Company seized leadership of the genre. Beginning with a game called Box Score in 1947, Williams manufactured a new baseball game nearly every year through 1973. Innovations by Williams over those twenty-five years include the first “running man” unit, which circled the bases as the player recorded hits, on Super World Series in 1951, one of the earliest games with multiple pitch types, Deluxe Short Stop, in 1958, the first game to allow additional playing time for reaching a certain score, Extra Innings, in 1962, and the first game to use electronic sound, Action Baseball, in 1971. United remained a close competitor and often copied Williams innovations, though quite possibly with the permission of Harry Williams himself seeing as he and United owner Lyndon Durant were old friends.

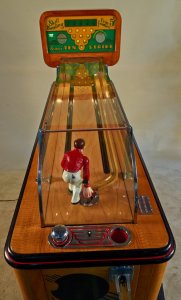

Ten Strike, a popular manikin bowling game from H.C. Evans and Company

While baseball remained the most enduring sports game of the period, manikin cabinets devoted to other games appeared from time to time. One of the most popular — both before and after World War II — was a bowling game called Ten Strike produced by H.C. Evans Company. Originally founded by Edwin Hood in 1892 as a carnival supplier, H.C. Evans became a pioneer of console gambling games under the founder’s son, Dick Hood, with the wildly popular Galloping Dominoes unit in 1936. By 1939, Evans was really feeling the heat of the anti-gambling lobby and decided to produce a console game incorporating skill-based elements, which led to the development of Ten Strike. In this game, the player uses a knob to position the arm on a mannikin holding a steel ball and then presses a button to launch the ball at a set of miniature bowling pins. The game remained in continuous production from 1939 to 1953 — with the exception of the war years — and entered production again in 1957 as the two-player variants Ten Pins and Ten Strike from Williams after that company bought the rights from Evans in 1955.

Another company to invest heavily in sports games was International Mutoscope, known for being one of the premiere innovators in the field of coin-operated novelty machines. In the early 1940s, the company deployed the earliest known coin-operated hockey game, Play Hockey. Presaging the the ball-and-paddle video games that rose to prominence in 1973, this game placed two players in control of manikin hockey goalies at either end of a long table. Each player could swing his goalie’s stick by rotating a knob, and the objective was to knock a ball into the opposing player’s goal. In 1948, the company deployed another unusual sports game, a boxing title called Silver Gloves. In this game, each player controls a boxer through a lever that allows him to move left and right and a trigger that allows him to punch. The goal is to knock the opposing player’s boxer down.

Goalee, a hockey game by Chicago Coin

Perhaps the company that experienced the greatest success with non-baseball manikin sports games was Chicago Coin. The story of Chicago Coin is intimately tied to that of Genco, as the founder was yet another brother of the three men that established that company and was actually responsible for getting the family into the industry in the first place. Samuel H. Gensburg was born in Russia in 1893, but the family immigrated to the United States when he was three years old and settled in Pittsburgh. A natural businessman, Gensburg helped out in his father’s grocery store for a time until he decided he wanted to open his own store at sixteen. Before long, his store was outperforming his father’s, and he opened a second store the next year followed by a nickelodeon cinema the year after that when he was just eighteen. At roughly age 20, Gensburg left Pittsburgh to seek new opportunities in the Western United States, but those plans ended in Chicago when he met, fell in love with, and ultimately married Dora Wolberg in 1919. He worked as an order filler for Sears for a time and then moved to Iowa to run a grocery store.

Before long, Sam decided that he could make better pinball machines than his brothers and established Chicago Dynamic Industries as a manufacturer of games marketed under the Chicago Coin name. The company started making replacement boards for popular existing games like Ballyhoo before deploying its first original pin table, Blackstone, in 1933. Two years later, the company experienced success with Beam-Lite, the first pinball game with a lighted playfield and a 5,000-unit seller. Like Genco, Chicago Coin prided itself on improving on the ideas of others rather than making important technological innovations itself, so the company rarely had a leading game in the market. One of its pingames, however, a 1947 flipperless release called Kilroy, sold a remarkable 8,800 units, the most of any pin game between World War II and the first licensed games of the mid 1970s.

In addition to pinball, Chicago Coin aggressively entered every novelty category in existence, which guaranteed that even though few of its products were leaders in their field, the company remained generally successful based on the sheer volume of its output. Therefore, it is no surprise that the company quickly embraced sports games after World War II. In 1946, Chicago Coin released a game called Goalee [sic], an enhancement of the International Mutoscope Play Hockey game that replaced the dials with levers and included an electric motor, thereby allowing a single player to challenge a hardware-controlled opponent. Popular for years after its debut, Goalee brought Chicago Coin over half a million dollars in revenue. The next year, the company expanded its sport line into basketball with Basketball Champ, in which one player controlled a player trying to make a shot on the basket and the other player controlled a defender attempting to block the shot. While manikin sports games like these achieved some popularity, however, it was larger table sports games that fueled a new expansion of coin-operated amusements into bars and taverns in the 1950s.

Bowling, Bumper Pool, and Shooting Galleries

Shuffle Alley from the United Manufacturing Company, which ushered in a whole new category of coin-operated amusements

The decline of pinball in the postwar era was not just due to the game being outlawed in major markets like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Just as damaging was the continuing stigmatization of the game as a front for organized crime due to the production of payout models such as Bally’s bingo games. As a result, many legitimate businesses were hesitant to allow any pingames on their premises, denying distributors and operators the same access to bars and taverns they had enjoyed during the Depression. Therefore, coin-operated amusement manufacturers urgently needed to develop new table games to stay relevant in postwar America. The solution to this problem came from Lyn Durant and his United Manufacturing Company, which had the good fortune to develop a new type of game just as a new fad began sweeping the country.

In October 1949, United deployed a bowling game called Shuffle Alley in which the player launched a small metal-cased object similar to a hockey puck down an eight-foot lane to trigger switches on the playing field that would cause suspended pins to retract to simulate being knocked down. Similar coin-operated games had appeared as far back as the 1890s, but had never really caught on in a big way before. This time, however, things were different. For one, United melded its bowling game with some of the most popular features of the pinball table such as electromechanical engineering, totalizer scoring, and a colorful, lighted backglass. More importantly, however, American Machine and Foundry (AMF), a major defense contractor looking to diversify its business, deployed the first automatic pinsetter for bowling alleys in 1951. Spurred by this innovation, bowling quickly became one of the most popular competitive sports in the United States, and new bowling alleys opened across the nation. With bowling so popular, bar owners that would never think of hosting a pinball table due to their sinister reputation were soon clamoring to have a shuffle alley in their establishments. United sold over 10,000 units of its Shuffle Alley game and was quickly joined in the market by other companies like Chicago Coin and Genco, but the dominant company in the field was Bally, which by the mid-1950s was releasing a new game every other month in a variety of configurations to fit the needs of bars and taverns of all shapes and sizes. Although introduction of new models declined after 1955 as the market neared saturation, shuffle alleys continued to be produced into the 1990s.

Just as the shuffle alley began to decline, another new concept appeared to keep the tavern market going. Before the Great Depression, the game of pocket billiards had been one of the most popular table games in the United States. So popular, in fact, that in the late nineteenth century betting parlors — called “poolrooms” at the time — often featured billiard tables so patrons could pass the time between horse races. As a result, Americans soon began referring to the game of pocket billiards as pool. During the Depression, pool entered a long period of decline that continued after World War II and did not end until the 1960s. In the meantime, manufacturers looked for other ways to keep the pool table relevant.

In May 1955, a Bay City, Michigan, company called Valley Manufacturing, originally established as a shuffleboard manufacturer in 1944, introduced a new billiards game called bumper pool. Rather than featuring pockets around the perimeter of the table, this game features just two holes set into either end of the table, one for each player. Upon inserting a dime, each player is provided a cue stick and five balls, which he has to shoot into the hole on his opponent’s side of the table. In the middle of the table are eight strategically placed bumpers to make shots more difficult. In 1954, no coin-operated pool games had been introduced into the market, but after Valley’s game took off, a whopping thirty games debuted before the end of the year. In 1956, the number of new games jumped to 52, by far the most models introduced of any type of amusement machine that year. Subsequently, the number of new bumper pool models declined precipitously as the brief fad ended. In 1957, however, both Valley and another firm called Fischer Manufacturing put a coin slot on a traditional six pocket pool table, bringing coin control to the standard billiards industry. As interest in pool revived in the 1960s, coin-freed pool tables became one of the pillars of the coin-operated amusement industry.

Air Raider from J.H. Keeney and Company, a popular target shooting game during World War II

Another game that experienced increasing popularity both during the Depression and in the post-war period was the coin-operated target shooting game, in which a player uses a gun-shaped controller to aim and shoot at targets. Shooting galleries were a popular destination in Victorian England, so it should come as no surprise that the earliest coin-operated rifle games appeared — like so many other coin-operated machines — in Great Britain in the 1880s and 1890s. The earliest known game of this type, in which inserting a coin would release the firing mechanism on an actual rifle that fired either pellets or real bullets, was created by Englishman William Reynolds in 1887, but it proved unsuccessful. Over the next several years, innovations in the field centered around the countertop trade stimulator models until the next major breakthrough in full-sized target shooting, the electric rifle, was patented by Englishman J.L. McCullogh in 1896. This rifle did not fire a projectile, but could be attached to a target via wires and register hits by determining the position of the gun relative to the target through the use of wipers and contacts. Popular in both Great Britain and the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, electric rifle games ultimately faded from the public consciousness as the arcade fell out of favor in the 1910s.

In the mid 1920s, the electric rifle returned to prominence in the United States thanks to the efforts of William Gent. Born in Rockford Illinois in 1871, Gent entered the coin-operated machine business in 1903 through the Buffalo firm of Mark Wagner & Company. In 1906, Gent moved to Cleveland to become the manager of the United Vending Machine Company, which was reorganized as the William Gent Vending Machine Company in 1917. As coin-operated games returned to prominence in the 1920s, Gent, by then one of the most influential entrepreneurs in the coin-op industry, decided to redesign the old electric rifle concept by replacing the plain circular target on a cast-iron lollipop stand with a wooden cabinet featuring an array of targets such as ducks that “quacked” when hit and planes with propellers that would spin when they were shot. Gent marketed this game as the Electric Rifle.

In 1929, a Canadian inventor named Henry Clavir created his own twist on the shooting game with Radio Rifle, the first game to employ targets projected on a screen. In this game, a rifle sits atop a large metal box housing a roll of film and a projector. Upon the insertion of a nickel, the projector turns on and beams the top image on the film roll onto a surface. The player receives five shots, and each time he pulls the trigger, a needle inside the machine synced to the position of the gun punctures the film, which looks like a bullet hole on the projected image. After the player takes all his shots, the machine cuts the target off the film roll and vends it to the player as a souvenir.

The Rayolite Rifle Range, perhaps the first target shooting game utilizing a light gun

Gun games using contacts and needles were ultimately superseded by guns using light sensing technology. The earliest patent for a light gun was filed in 1920 by an Englishman named W.G. Patterson, but he appears not to have created any games based on his invention. Instead, a small Tulsa, Oklahoma, firm called the Rayolite Rifle Range Company pioneered the light gun game. Established in 1934, the company was built around the Ray-O-Lite System, patented by Charles Griffith in the same year the company was founded, in which a specially-made gun shoots a narrow beam of light when the trigger is pulled that is picked up by a solar cell attached to a target to register a “hit” on the object. The company created the Rayolite Rifle Range around this system with a duck as the target, which was manufactured starting in 1935 by the Seeburg Corporation. When the game proved successful, Seeburg continued to create other popular light gun games over the next decade and a half such as Chicken Sam (1939), Shoot the Bear (1947), and Coon Hunt (1952).

With World War II looming in Europe by the end of the 1930s, the light gun reached the apex of its popularity as games with a military theme took center stage, led by the releases of J.H. Keeney and Company. In 1939, Keeney deployed Anti-Aircraft Machine Gun, which featured a large metal machine gun replica and targets projected onto a screen. The game proved so popular that a number of variants were released over the next two years such as Air Raider and Shoot Your Way to Tokyo. Meanwhile, Seeburg created war-themed variants of its popular Chicken Sam game like Trap the Jap and Hit the Siamese Rats. The popularity of these light gun games peaked in early 1942, after which the production of new amusement machines was curtailed by the entry of the United States into the war. Light gun games failed to enjoy the same success after the war, superseded by a new gun game concept pioneered by an engineer named Eldon Dale.

An early Dale gun game manufactured by the Exhibit Supply Company

A native of Missouri living in Long Beach, California, Dale developed his own twist on the old electric rifle game by having the gun swivel on a stand attached to a metal rod extending under a greatly truncated playfield. If the player lined up the rifle perfectly with a target, the metal rod would touch it, and a pull of the trigger would complete a circuit to register a hit. To give the illusion of a large playing area within the small cabinet, Dale used a mirror to reflect the targets in a manner similar to a submarine periscope. Before the Dale system, both light gun and electric rifle games required a great deal of space to place enough distance between the player and the target, making them suitable only for larger venues. The Dale game, however, fit in a cabinet no larger than a pinball table, making gun games suitable for a variety of locations.

Dale created his gun game at his own Eldon Dale Manufacturing Company, but it was released nationally by the Exhibit Supply Company as Shooting Gallery in March 1950. Once the game was in the field, however, Exhibit discovered that the Dale mechanism could easily shock the player, so the company redesigned it and released a whole line of games in October 1950 featuring the same basic setup but different themes and cabinet art. Before long, Genco and United were making versions of the Dale gun game as well. Production of Dale games peaked in 1954, a year in which fifteen different gun games were released and manufacturers built over 7,000 cabinets in just seven months. Although fewer games were produced per year after that, target shooting games remained an important draw not just at arcades, but at a wide variety of new venues that began appearing by the end of the 1950s.

Fun Spots and Playlands

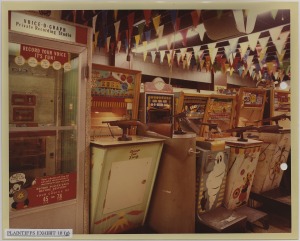

Gun games and a sound recording booth at the Wonderland Arcade in Kansas City, Missouri, 1968

Throughout the 1950s, the United States experienced great population shifts as the development of the Interstate Highway system and the rise of an automobile-centric culture led many families to leave life in the big city for rapidly developing suburban communities. As a result, traditional arcades once again entered a period of decline, trapped as they were in newly blighted inner city neighborhoods. Simultaneously, as the youth population of the United States exploded through the onset of the Baby Boomer generation, all manner of new entertainment venues opened their doors in suburbia such as bowling alleys, roller and ice skating rinks, public swimming pools, drive-in theaters, and amusement parks. Collectively referred to as “fun spots,” there were an estimated 21,093 such venues around the country by 1958 taking in $2 billion annually. With the inner city arcade once again falling by the wayside and many bars only amenable to select pieces like shuffle alleys, these fun spots were vitally important to the continued well-being of the coin-operated amusement industry.

During the Depression, coin-operated amusements had catered to adults looking to forget their troubles for an hour or two through the relatively cheap thrills of the penny arcade. With amusements expanding heavily into fun spots in the 1950s, however, the emphasis shifted to providing fun for the whole family — and especially for children. Therefore, sports games, gun games, driving games, ball bowlers (a variation on the shuffle alley first introduced by United in 1956 that sported longer lanes and miniature balls rather than pucks), snack vending machines, and novelty pieces like instant photo booths and voice recorders all played an increasingly prominent role in the industry. Perhaps the greatest indicator of the importance of children to the new amusement arcade, however, was the rapid development of a new segment of the business during the decade, the kiddie ride.

In 1931, Otto Hahs, owner of the Hahs Machine Works in Sikeston, Missouri, decided to build a mechanical horse to entertain his children. Before long, children from around the neighborhood were showing up in droves to ride this contraption, so Hahs decided to attach a coin chute and a timer to turn it into a commercial product. Hahs experienced some success in selling his rides to arcades and amusement parks — as well as exhibitors at the 1933 Chicago and 1939-40 New York World’s Fairs — but they remained a niche attraction. In 1949, however, the Exhibit Supply Company engaged Hahs to design kiddie rides that it would mass produce, signalling a new phase in the business.

Initially, Exhibit followed Hahs’s lead in selling the rides to amusement parks and arcades, but the company soon felt that a better target for the product would be department stores, which generally hosted rides such as trains, boats, and ferris wheels in their toy sections during the Christmas season to lure in holiday shoppers. Store owners were skeptical at first, but a 22-year-old entrepreneur named Matty Carbone ultimately convinced the Chicago department stores Goldblatt and Weiboldt to install a few kiddie horse rides, which proved to be a great draw, often taking in $100 per horse per week. Other stores quickly installed their own rides, and by 1953 there were 8,200 kiddie rides in operation around the country, mostly horses, but also other conveyances like cars, boats, and rocket ships. Exhibit Supply remained a leading firm, but Bally invested heavily in kiddie rides as well. By 1959, the popularity of kiddie rides and similar amusements had paved the way for yet another new arcade venue, the playland, which would be situated in a high traffic area of a department store, discount house, or shopping center and offer a full range of coin-operated rides and games aimed at children.

Hank Ross, co-founder of the Midway Manufacturing Company

The new demand for arcade pieces to fill fun spots and playlands aided the growth of the last significant coin-operated amusement manufacturer founded before the dawn of the video game era, and the first such company since the start of the Great Depression not established to focus on pinball. Mechanical engineer Marcine Wolverton, who went by “Iggy” because many people considered Marcine to be a girl’s name, designed aircraft ordinance during World War II and then entered the coin-op industry after its conclusion, briefly working at jukebox maker Wurlitzer before landing at the United Manufacturing Company. In 1947, he was joined there by electrical engineer Hank Ross, who had previously worked for Exhibit Supply. When United began to encounter difficulties in the late 1950s, Wolverton and Ross, regarded as two of the company’s top designers, decided to strike out on their own. Scraping together $5,000 dollars, they formed an equal partnership in October 1958 based in the Chicago suburb of Franklin Park, Illinois, called the Midway Manufacturing Company, named for the nearby Midway Airport.

Wolverton and Ross planned to survive as a small company in the highly competitive coin-op industry through a low overhead factory operation that would allow them to undercut competitors on price. To that end, they leased a small 5,000 square foot manufacturing facility and fabricated most of their factory installations and game parts themselves. Working long hours at the plant during the day, both men also attended night school to brush up on business. In January 1959, the duo began production of their first game, a shuffleboard with a rebound feature called Bumper Shuffle, followed in May by a unique game called Red Ball in which the player presses buttons to launch balls at a bingo-style play field in the hopes of arranging them in various configurations to score points. In 1960, the company scored its first major hit with a pellet shooting game called Shooting Gallery and thereafter focused largely on gun games and pitch-and-bat baseball games, also adding a shuffle alley line in 1966 after moving to a larger facility in nearby Schiller Park. In 1964, Midway introduced two important innovations to Dale-style shooting games through a wild west themed game called Rifle Champ, automatic speed control that causes the targets to speed up as the player scores more points and targets that appear to glow through the use of fluorescent paint and a black light. Glowing targets became standard in most target shooting games going forward, one of the few major innovations in an industry beginning to show signs of stagnation. By 1965, Midway’s innovative game designs and manufacturing skill had brought the company enough success that the trade press recognized the firm as one of the “big five” manufacturers of coin-operated amusements alongside Gottlieb, Bally, Williams, and Chicago Coin, the only significant companies to survive — and sometimes just barely at that — a brutal shakeout of the industry in the late 1950s.

I always love the use of mirrors in arcade games. I’m still trying to figure out a couple things about Tornado Baseball, which used the whole color reflection thing.

Speaking of, that’s by Bally, and I’m glad to finally figure out what they were about. Was expecting something grander, but that’s just the way of things. Being the new kids on the block they were following a trend, but quickly transcended it, and I think they’re a lot more important than most give them credit for.

Good to see the general light gun information coming out now as well. I feel like I’ve completely skipped over video light gun games that did something different than the electro-mechnical ones, but these things were pretty advanced. More research to be done, as always. And great post, like always! (No questions this time)