During the Depression the coin-operated amusement business flourished by virtue of being cheap. With every last cent precious, a pinball machine that could provide a few minutes entertainment for a mere penny was the closest thing to a luxury many people could afford. In the 1950s, however, the economy was booming, the population was growing and dispersing, and there were many new activities to occupy the time of the prosperous suburban middle class. As a result, coin-operated games morphed from the star attraction of the Sportland to a mere sideshow at a fun spot or department store playland.

This is the penultimate chapter in a six-part examination of the coin-operated games industry before the dawn of the video game era. Principle sources this time around include Pinball 1: Illustrated Historical Guide to Pinball Machines by Richard Bueschel, The History of Coin-Operated Phonographs. 1888-1998 by Gert Almind, Special When Lit: A Visual and Anecdotal History of Pinball by Edward Trapunski, King of the Slots: William “Si” Redd by Jack Harpster, Bally: The World’s Game Maker by Christian Martels, the article “A Profits Jackpot in Slot Machines” in the March 13, 1977, edition of the New York Times, the article “Gaming Giant Has Checkered Past, Local Ties” in the July 15, 1979, edition of the Boca Raton News, the article “The Seeburg’s Term It Automatic Record Playing, But the Public Calls It the Jukebox” in The American Swedish Monthly, the article “Money in the Box” in the October 27, 1958, edition of Time Magazine, numerous articles from the 1950s and 1960s in Billboard Magazine, the Internet Pinball Machine Database, Bally’s official history from its (now defunct) company website, In re Bally’s Casino Application, 10 N.J.A.R. 356 (1981), and the research and personal recollections of British operator and coin machine historian Freddy Bailey.

The Rise of the Jukebox

The Wurlitzer Model 24 (1937), one of the most successful jukeboxes before World War II

Coin-operated music machines were a mainstay of arcades from the very beginning, with phonographs in particular being one of the major draws of the earliest amusement parlors of the 1890s. After the phonograph came down in price enough that practically anyone could afford one, it largely disappeared from the arcade scene, but other musical devices took its place. Perhaps the most popular machines in the early 1900s were the coin-operated player pianos and organs. These could be quite elaborate at times, as epitomized by the Mills Violano Virtuoso, invented by Henry Sandell, which combined a self-playing violin and piano in a single large cabinet and sold between 4,000 and 5,000 units between 1911 and 1930. The advent of electrical recording, however, pioneered at Western Electric in 1924, greatly increased the quality of recorded music while also allowing the playback of recordings to be amplified. This posed a significant threat to the instrument manufacturers, a challenge first answered by the Automatic Musical Instrument Company (AMI).

AMI began life as two closely linked companies in 1909, the National Piano Manufacturing Company, which built coin-operated musical instruments, and the National Automatic Music Company, which operated them. Its most prominent product in its early years was a player piano that could automatically switch between eight different music rolls, and by the mid 1920s the companies had around 8,500 machines on location. In 1925, the two companies merged into one corporate entity, but did not adopt the name AMI until 1927. That same year, AMI introduced the National Automatic Selection Phonograph, a record player hooked up to a loudspeaker and a selector that could switch between ten records. The AMI unit was not the first multi-selection record machine, but it was the first device to combine a record player, a selector, loudspeaker amplification, and a coin slot. By 1930, 12,000 Automatic Selection Phonographs had been installed, and a new segment of the coin-op industry was born.

In the 1930s, several prominent coin-op manufacturers tried their luck at the Jukebox business including Mills and Rockola, but the leading company was Wurlitzer, a musical instrument manufacturer founded by Rudolph Wurlitzer in 1853 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Starting as an importer of European Instruments, the company became a major manufacturer by supplying instruments to the United States Army during the American Civil War. When the first fairground organs began to appear in the 1890s, Wurlitzer invested in one of the early manufacturers, the North Tonawanda Barrel Organ Factory, in 1897. In 1909, Wurlitzer bought the company outright, shifted all production to New York, and developed an organ for motion picture houses that proved highly successful after being released the next year. With electrical recording paving the way for “talkies” in the cinema and thereby making theater organs redundant, Wurlitzer nearly went out of business in the late 1920s and turned to jukeboxes through purchasing the Simplex Manufacturing Company in 1933, which had developed a multi-selection unit. Simplex owner Homer Capehart became the general manager of Wurlitzer and guided the company back to success. By 1936, Wurlitzer had placed 44,000 jukeboxes on location, and the company continued to dominate the market until the late 1940s, when it was dethroned by the J.P. Seeburg Corporation.

The Seeburg M-100A,which revolutionized the jukebox business in 1948

Born in Gothenburg, Sweden, in 1871, Justus Sjoberg completed a course of study at the Chalmers Technical Institute and then immigrated to the United States in 1887. In the U.S., he took classes at a Chicago night school, studied technical subjects at the Lewis Institute, and took drawing and design classes at the Chicago Art Institute. When he became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1892, he changed his last name to Seeburg. Seeburg’s first job in the United States was at the C.S. Smith & company piano factory in Chicago, where he learned the musical instrument manufacturing trade. Several years later, he became the superintendent at another piano maker, the Cable Company, before joining with a partner to establish the Kurtz-Seeburg Corporation in Rockford, Illinos, to manufacture piano actions. In 1902, he returned to Chicago to establish the J.P. Seeburg Piano Company, which enjoyed great success as a manufacturer of coin-operated pianos and theater organs.

When AMI debuted the National Automatic Selector Phonograph, Seeburg responded in 1928 with its own eight-record machine, changed its name to J.P. Seeburg Corporation to distance itself from its musical instrument roots, and switched its focus to the jukebox business. The Depression hit Seeburg hard, however, and forced the company into receivership in 1931. In response, Justus expanded his company into nearly every device that could be based around a coin slot, including vending machines, washing machines, parking meters, and arcade pieces like the Rayolite gun games, which restored the company’s financial situation by 1934. That same year, Justus entered semi-retirement and his son, Noel Marshall Seeburg, took over as president. Seeburg remained number two in jukeboxes until 1948, when it deployed the M-100A, the first jukebox able to play one hundred different selections. Arriving just before the advent of high quality multi-track tape recording technology, the introduction of the small and durable 45 rpm record, and the explosive popularity of Rock ‘n’ Roll, the 100A completely transformed the coin-operated machine industry and allowed Seeburg to corner 70% of the jukebox market by 1960.

By the mid-1950s, over 500,000 jukeboxes had been installed across the United States, and the sale and operation of coin-operated music and games, largely separate before World War II, consolidated around the music distributors and operators, who placed an emphasis on jukeboxes installed at bar and tavern locations, leaving comparably little room for less profitable classes of machines. This power shift is perhaps best reflected by changes in the trade organizations of the period. The coin-operated machine industry first organized nationally during the resurgence of the late 1920s, rallying around the first industry trade magazine, Automatic Age, which started publishing in 1925, and the first nationwide trade organization, the National Vending Machine Operators Association, established in 1926 through the efforts of Chicago coin-operated scale manufacturer and operator E.H. Funke. The association held the first national coin machine trade show that February at the Great Northern Hotel in Chicago, which became an annual tradition. The show took place in Chicago in even-numbered years and another major city like Cleveland or Detroit in odd-numbered years, but in 1931 the manufacturers revolted, tired of paying freight to bring their products to other cities when they were nearly all located in Chicago already. These companies therefore banded together to create the National Association of Coin Operated Machine Manufacturers — later shortened to Coin Machine Industries (CMI) — which hosted an increasingly lavish and well attended coin machine show at the Sherman Hotel in Chicago through the rest of the 1930s.

After World War II, CMI fell apart. The vending machine trade came into its own during World War II as factories installed food and drink machines to help workers keep up their strength while churning out military equipment. Feeling their oats, the manufacturers of those machines broke away to form the National Automatic Merchandising Association and launched their own show in 1946, which routinely outdrew the CMI coin show in the late 1940s. That left amusements and jukeboxes for CMI, but the jukebox makers never liked exhibiting at the coin show because they were forced to turn down the volume of their machines and had a difficult time selling them to potential customers. The jukebox makers increasingly retreated to private suites in neighboring downtown hotels to show their products, and as the jukebox grew ever more influential in American daily life, the companies involved in the business increasingly felt they no longer needed the CMI.

Two events cemented the end of CMI. First, the organization announced in 1949 that it would no longer represent companies like Bally that produced payout machines. In protest, Bally president Ray Moloney organized a new trade organization, the American Coin Machine Manufacturers Association (ACMMA), which announced its own trade show set for May 1950. Meanwhile, jukebox route operators George Miller of Oakland, California, and Al Denver of New York City forged a loose collection of state and local operators associations into an alliance called the Music Operators of America (MOA) in 1948 to combat efforts to eliminate the traditional music royalty exemption afforded to jukeboxes. In 1950, the MOA decided to stage its own trade show in November, and CMI, which now stood for Coin Machine Institute, cancelled its show that June when it became clear that distributors and operators did not want to attend another convention so soon after the ACMMA show and were far more interested in clustering around the jukebox and record companies at the MOA convention later in the year. The short-lived ACMMA disbanded in 1951, while CMI tried one more time to stage a show in 1952, but the show floor was largely filled with purveyors of kiddie rides, and attendance was poor. As CMI floundered before the onslaught of the jukebox, the industry it represented also began to shrink.

Death and Turmoil in Amusements

J. Frank Meyer, who led the Exhibit Supply Company into coin-operated machines

In August 1948, Jack Keeney, the pioneering head of J.H. Keeney and Company, passed away not long after suffering a debilitating stroke. J. Frank Meyer, the man who turned the Exhibit Supply Company into a coin-op powerhouse, died that November, just a few months after his trusted sales manager Perc Smith. In 1953, Dick Hood passed, and the Hood family relinquished control of H.C. Evans and Company for the first time. In 1956, William Rabkin, founder of the constantly innovating International Mutoscope, died in a fall from the window of his sixth floor apartment, possibly due to a dizzy spell brought on by high blood pressure. Once vital contributors to a thriving coin-operated amusement business, these companies bereft of their founders and/or primary movers soon looked for greener pastures. International Mutoscope filed for bankruptcy in 1960 and while it managed to limp along for a few more years was never a potent force in the business again, while H.C. Evans attempted to enter the surging jukebox business by purchasing the Mills phonograph division in 1948 and failed so miserably that the company was forced to close in 1955. J.H. Keeney chose to focus on vending machines and slots and slowly decreased its amusement output before releasing its last pinball game in 1963, while even Exhibit Supply, which under Meyer had blossomed into the leading amusement manufacturer of the 1920s, chose to focus on other areas of manufacturing.

During World War II, Exhibit had developed a new switch, the electro-snap, that proved so useful that the company created a subsidiary called the Electro-Snap and Switch Manufacturing Company to continue selling switches to the military after the war. By 1957, the switch business completely overshadowed Exhibit’s dwindling amusement business, so the company chose to end amusement equipment manufacturing and give the factory space over to Electro-Snap. This led to the resignation of company president Sam Lewis, one of a series of short-lived caretakers to run the company after Meyer’s death, and the appointment of arcade division head Chester Gore to run the company. As Exhibit card vendors continued to be popular, Gore moved the company to a larger factory in 1960 to commence manufacturing of card machines again, but it never returned to other amusements. Gore continued to run the company until selling out to a man named Paul Marchout in 1979, who was only interested in the name and effectively shut the company down.

The most shocking industry death of the decade occurred on February 26, 1958, when Ray Moloney, president of the Lion Manufacturing Company and its Bally subsidiary, died suddenly of a heart attack at fifty-eight. From the launch of Ballyhoo in 1932, Moloney had built Bally into one of the largest and most important coin-operated amusement companies, a fully integrated manufacturer of slot machines, payout pinball machines, shuffle alleys, kiddie rides, and various other arcade pieces. Bally not only manufactured coin-operated machines, but through a host of subsidiaries such as the Grand Woodworking Company, Como Manufacturing Company, Ravenwood Screw Machine Corporation, Comar Electric Company, and Marlin Electric Company, it built nearly all the specialized parts and mechanisms used in its products. Most recently, Moloney had led Bally into the vending machine business in 1956 with a well received hot and cold drink machine and established a new subsidiary, Bally Vending Corporation, to sell it.

Moloney’s death threw Bally into turmoil. His entire estate, including Lion and its subsidiaries, was placed in a trust administered by the Chicago-based American National Bank and Trust Company. Longtime Bally executive Joseph Flesch took over as president, but he relinquished control to Moloney’s sons, Ray Jr. and Donald. By that time, the decline in the sale of bingo machines brought on by the 1957 Supreme Court decision banning payout pinball machines had significantly impact Bally’s bottom line, and the company was losing money. American National therefore felt it was in the best interest of the estate to liquidate the firm to pay off debts and estate taxes. Moloney’s sons argued that allowing Bally to develop and sell new slot machines would restore Lion to profitability, but the bank had no interest in funding an operation it assumed would have deep ties to organized crime. The Moloneys bought themselves some time by selling Bally’s highly successful drink vending machine business to Seeburg for $3 million in 1961, but the next year American National decided it was time to dissolve the firm. Bally ultimately survived, however, through the intervention of Bill O’Donnell.

Bill O’Donnell, the man who saved Bally

Born in 1922, William Thomas O’Donnell was educated at Loyola Academy and Sullivan High School, but was forced to drop out in 1939 at age seventeen to support his family by joining the Underground Construction Company, where his father had served as superintendent before dying in 1929 at the age of thirty-five, to help build the Chicago subway system. After enlisting in the United States Marine Corps in 1941 and serving in the Pacific Theater during World War II, O’Donnell briefly served as a postal worker after being discharged in 1945 before a cousin who served as Ray Moloney’s bookmaker suggested he seek employment with Bally. O’Donnell joined the firm in 1946 to work in the purchasing department before Moloney named him assistant sales manager six months later. In 1951, Moloney promoted O’Donnell to sales manager, and upon Moloney’s death American National named him to Lion’s board of directors. O’Donnell subsequently played an active role in trying to save Bally through a management buyout, but he could not find a single bank willing to finance a slot machine company due to fears of ties to organized crime. He therefore turned to Bally distributors for support.

Runyon Sales, a successful New Jersey distributor fronted by Abe Green and Barnett Sugarman, proved amenable and brought in two other investors of its own, a Brooklyn pool table manufacturer named Irving Kaye and a well-connected former vending executive named Sam Klein. A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Klein served in the Army in World War II and then entered the family business, a cafe. In 1954, he purchased the Stern Vending Machine Company of Cincinnati, which he later sold in 1960 to a firm called Emprise Corporation for $1.5 million. At that time Emprise owner Lou Jacobs asked Klein to find other companies for him to purchase, leading him to talk to Green about buying Runyon. The deal never materialized, but Green remembered Klein’s connections when it came time to make the Bally deal. Although hesitant at first, Klein ultimately agreed to come on board and convinced Jacobs to finance a portion of the purchase. This allowed O’Donnell, Klein, Green, Kaye, and Sugarman to form K.O.S. Enterprises and buy certain assets of Lion Manufacturing and the Bally name on June 17, 1963, for $2.85 million. K.O.S. subsequently changed its name to the Lion Manufacturing Corporation and named Bill O’Donnell president. Klein, the largest shareholder of the new corporation, became executive vice president. Subsequent to the purchase, O’Donnell turned his attention to launching the new slot machine Moloney’s sons had failed to complete.

A Revolution in Slot Machines

Money Honey, the first electromechanical slot machine

The slot market Bally hoped to rejuvinate entered the 1960s in crisis. The passage of the Johnson Act coupled with a contemporaneous ban on the manufacture of slot machines by the state of Illinois had virtually destroyed the industry at the beginning of the 1950s, which could now only engage in limited production of machines for Nevada and a few scattered counties and gray markets in other states. The leader remained Mills, which had transformed greatly since its penny arcade days. Company founder Herbert Mills died in 1929, though by then he had already divested much of his authority to his sons, Fred, who served as general manager, and Herbert Jr., who ran production. Fred succeeded his father as president and led the company into vending machines in 1935 in alliance with Coca-Cola, for which it produced one of the first automatic cooled bottle-dispensing soda machines. The company subsequently established the Mills Automatic Merchandising Company in New York to sell gum dispensers and similar machines. In 1943, Mills Novelty changed its name to Mills Industries, Inc. to reflect its more diverse range of activities, which now including vending machines, jukeboxes, slots, and refrigeration equipment.

Fred Mills died in 1944 and was succeeded by Herbert Jr. as president, who decided to separate slot machine sales from the rest of the company by establishing Bell-O-Matic Corporation in 1946. Even with this split the company remained focused on slots until the passage of the Johnson Act, which necessitated an increased focus on vending machines. The company generally struggled after the War, however, and filed for bankruptcy in 1948. The company’s creditors appointed a man named A.E. Tregenza executive vice president of Mills Industries, who sold the jukebox division and pushed hard for expansion in vending, freezers, and ice cream machines. Ultimately, he helped arrange a sale of the company in 1954 to a group of investors led by Richard Dooley. The new investors were not interested in slot machines, so Herbert Jr. and his brother Ralph retained Bell-O-Matic, which had shifted its headquarters to Nevada in 1951.

Mills’ primary competition in slot machines continued to come from O.D. Jennings and its successor, Jennings & Company, established to take over the assets of the original firm after Ode Jennings died in 1953. In 1957, Jennings became a subsidiary of the Hershey Manufacturing Company, and by the early 1960s Jennings slot machines represented 80% of Hershey’s total manufacturing output. Mills and Jennings each held roughly 35%-40% of the slot machine market, with most of the remainder going to Ace Manufacturing, the successor of a firm called the Pace Manufacturing Company. Founder Ed Pace had started in slots in 1926 as a purveyor of used machines before buying out another company to start his own manufacturing the next year. Pace Manufacturing released several popular models in the 1930s and continued operations until the passage of the Johnson Act in 1951, after which Pace retired. Coin-op veteran Harold Baker took up the manufacturing of Pace slot machines at that point, and when he died two years later, Ace took over the operation. In the early 1960s, Ace controlled about 15% of the market.

In 1963, Illinois repealed its slot machine manufacturing ban, and O’Donnell was ready to take Bally back into a market it had abandoned in 1949. Because the Johnson Act had been passed so soon after the complete halt in slot machine production brought on by World War II, most machines in use at Reno and Las Vegas casinos still relied on decades old mechanical technology. These machines were burdened by several limitations, most notably a payout cap of twenty coins, the most that could fit in a coin tube. Larger payouts had to be awarded by an attendant who came over to verify the win, and this extended halt in play created a natural ending point after which the patron would often leave. By incorporating a hopper controlled by an electrical circuit, Bally’s new machines could regulate delivery of several thousand coins in a variety of payout combinations, thereby allowing faster, more exciting play sessions.

The hopper that proved so crucial to Bally’s new slot machine came to the company in a roundabout way thanks to a prominent Vegas distributor named Mickey Wichinsky. Starting as an operator in the Castskills in the 1940s, Wichinksy developed connections with both Runyon Sales and the mob-backed Las Vegas casino operations and moved to Las Vegas in 1956 to establish a distributor called Frontier Vending and take over as the Pit Boss of the Sands Casino, where he became the first person to install Bally machines in a Vegas casino. In 1960, Wichinkky financed the development of a new roulette table produced by Jack Lavigna and Clarence “Doc” Kaufman for the Acme Novelty Company. In addition to providing funding, Wichinsky, who started designing his own games on the side in 1957, also developed the first hopper mechanism for the machine. The roulette proved unsuccessful, but Kaufman also served as Bally’s distributor in southern Nevada and passed the hopper innovation along to the company. Bally built five prototype hopper machines by converting an old mechanical machine called High Hand and passed them along to Wichinsky, who had in the meantime bought out Kaufman’s business and now ran Bally’s southern Nevada distributor, the Bally Sales Company. The prototype proved poorly engineered, however, so Kaufman rebuilt it to create the Bally Model 742A. At first unable to win approval from the Nevada Gaming Commission for the 742A, Bally turned to England, where a law passed in 1960 had legalized slot machines in pubs for the first time. Cyril Shack of the Phonographic Equipment Company began importing the machines by the planeload, but felt that in order to garner mass market appeal, the 742A would need to have a proper name. He suggested Money Honey.

By 1964, Bally was in full production on Money Honey, but many Nevada casino owners were hesitant to buy the new machines, largely due to quality concerns and the expense of replacing their entire stock of machines at once, so production remained limited for the first few years and sales were mostly made overseas. Things changed in 1967 when a veteran Wurlitzer distributor named Si Redd established the Bally Distributing Company in Reno at O’Donnell’s behest with a mandate to sell Money Honey machines in northern Nevada. Redd took to installing up to twenty slot machines at area casinos free of charge and sometimes even offered to reinstall their old machines for free if the owners were not satisfied with the Bally machines. When operators saw their earnings per machine increase by as much as 400% with electromechanical slots, the logjam broke, and Bally took over the market. In 1968, Bally produced 94% of all the slot machines sold in the state of Nevada. Buoyed by this success, O’Donnell incorporated Lion as the Bally Manufacturing Corporation that year with the intent of taking the company public. A long Securities & Exchange Commission investigation followed to insure the company was not a front for organized crime, after which Bally became the first publicly traded coin-operated manufacturer on March 13, 1969.

Innovation in Pinball

Duette (1955) from Gottlieb, the first two-player pinball

Through all the turmoil of the 1950s as companies closed, prominent executives died, gambling devices faced legislation, and target demographics changed, one company continued on as it always had. David Gottlieb was known as a conservative businessman who rarely took risks and ran his affairs as if the entire coin-op industry could fall apart at any time. He therefore refused to chase novelty markets and fads, focusing on the amusement pinball trade that had served him well since Baffle Ball in 1931. While Ray Moloney at Bally expanded into the gambling business as fast as he could and eventually ceased building traditional pinball machines entirely in favor of bingo games, Gottlieb refused to release payout machines of any kind and publicly feuded with his counterpart at Bally, arguing that gambling machines only invited government interference.

Even as shuffle alleys and pool games dominated the first half of the 1950s, Gottlieb continued to focus its attention on pins. While an individual machine in this period might sell only 1,000-2,000 units, Gottlieb maintained an aggressive release schedule of between ten and twenty tables a year to become the dominant pinball manufacturer in the industry. Remarkably, nearly all of these tables were designed by a single man, Wayne Neyens. Born in Iowa in 1918, Neyens was attending Crane Technical High School in Chicago in 1936 when a coin-op company called Western Equipment & Supply came to the school looking to hire a draftsman. Neyens worked part time for Western until he graduated high school and then joined the company full time doing odd jobs in the shop and eventually becoming a line inspector. In 1939, he left Western in a salary dispute and joined Gottlieb as a tester. Neyens designed his first pinball game in 1949, and when flipper inventor Harry Mabs left the company in 1951 to work for Williams, Neyens took his place as Gottlieb’s principle designer.

Pinball experienced few innovations in the 1950s, but Neyens was responsible for most of them. Perhaps the most significant was the advent of multiplayer pinball, in which several players competed with each other for a top score. The key technological innovation that made multiplayer pins possible was the introduction of mechanical reels to tally the score in place of numbers lighting up on the backglass, which debuted in the Williams pin game Army-Navy in 1953. Gottlieb introduced the first four-player pinball machine, Super Jumbo, in 1954, but the game was not particularly successful due to the mistaken perception that four players were required to play the game. Neyens therefore went back to the drawing board and created the first two-player pinball game, Duette, the next year. Duette proved far more successful, and by 1956 multiplayer pinball machines had eclipsed single player pinballs and pool tables in sales at Gottlieb. Multiple players also justified a higher price per play, and along with bumper pool Gottlieb’s multiplayer machines led a transition from penny and nickel play to dime machines. In 1960, Gottlieb introduced another innovation on its Flipper table, the add-a-ball mechanism, created to circumvent laws in certain jurisdictions like Texas were a free play was considered a prize that transformed an amusement pinball into a gambling machine.

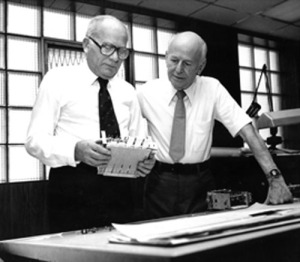

Sam Stern (l) and Harry Williams

While industry leader Gottlieb proved a model of stability in the 1950s and 1960s, the number two pinball company, Williams, underwent several profound changes that began when company founder Harry Williams met a man named Sam Stern. Working in the clothing business in 1931, Stern decided on the advice of friends to break into the coin-op industry as a route operator in Philadelphia and became a major player after becoming a Rockola jukebox distributor in the city in 1939. Eager to move further up the chain, Stern walked into Williams’s office in 1947 and brazenly asked to buy 49% of Williams Manufacturing, and Williams, who far preferred designing to managing, agreed to sell. Stern became a vice president at Williams in January 1948 and held the post for the next eleven years before orchestrating a buy-out of Williams in 1959 by Consolidated Sun-Ray, a New York retail conglomerate that operated a variety of businesses from drug stores to discount houses. Both owners were offered cash or stock in the deal. Williams opted for cash and left the company, while Stern took stock and replaced Williams as president of the renamed Williams Electronic Manufacturing Corporation. The merger with Sun Ray did not work out, however, and Williams became independent again in 1961.

Under Stern, Williams could never dethrone Gottlieb from the top of the pinball industry, but it maintained the Williams legacy by being the main innovator of the game in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Leading these developments were Harry Mabs, the flipper inventor who joined the company from Gottlieb in 1951, and flipper refiner Steve Kordek, who stayed at Genco, which became a subsidiary of Chicago Dynamic Industries in 1952, until the company shut down in 1959 and then worked briefly at Bally before joining Williams in 1960. In 1958, Mabs built a game called Gusher that featured the first “disappearing bumper,” a bumper that would lower into the playfield when hit. In 1960, he designed a game called Magic Clock that featured the first moving target on a pinball playfield. Mabs retired soon after, and in 1962 Kordek designed another innovative table called Vagabond that featured the first drop target on a playfield, a special type of standup target that drops below the playfield when hit. The next year, Kordek introduced another important innovation in Beat the Clock, multiball, the possibility of having more than one ball in play at the same time if the proper targets are hit. In 1966, another designer named Norm Clark gave Williams one of the biggest hits of the decade, a 5,100-unit seller called A-Go-Go that featured another new playfield mechanic, a captive ball spinner that spun around and dropped the ball into a hole with a random point value when trapped by the device. These tables helped transform pinball into a game of structure and sequence as the primary objective of the game became hitting a group of targets in a specific order or targeting a specific part of the playfield at a specific time to gain added benefits and bonus points. Ultimately, Williams’ expertise in pinball design attracted the attention of another major coin-op firm with ambitions to expand, the Seeburg Corporation, which had recently come under new management.

In the early 1950s, Herbert Siegel, a journalism graduate working for a Manhattan TV firm, and Delbert Coleman, a University of Pennsylvania law student, combined their resources to buy a stake in a soft drink company that they then swapped to acquire a Cleveland chemical company whose earnings they were able to double in ten months. Next, they set their eyes on Fort Pitt, a Pittsburgh beer brewing company established in 1906. Once Pennsylvania’s top brewer, Fort Pitt had been severely hamstrung by a series of strikes in the early 1950s and had sustained losses of over $1.8 million by 1955. These losses could be offset through a merger with a profitable company, however, so Siegel and Coleman courted the brewer’s longtime president, Michael Berardino, and arranged a merger in April 1956 with two coat companies owned by the Siegel family, Windsor Overcoat and the Jacob Siegel Company. After concluding this deal, Siegel and Coleman marshaled the combined financial might of the new conglomerate to purchase Seeburg that December, which by then enjoyed average yearly sales of around $30 million and average yearly earnings of $2.6 million. With these acquisitions complete, the duo orchestrated a management coup in March 1957, removed Berardino from the company, and secured Siegel’s appointment as chairman of the board and Colemen’s appointment as president of Fort Pitt. The duo then sold off the brewery business that November and changed the name of the parent company to Seeburg Corporation in April 1958.

After securing their hold on Seeburg, Siegel and Coleman initiated an aggressive expansion plan intended to involve the company in nearly every coin-operated field. In 1958, the company purchased the cigarette vending machine business of Eastern Electric. In 1961, it added Bally’s drink vending business. Several more drink and cigarette vending machine purchases followed along with the Kinsman Organ Company, which together made Seeburg the largest manufacturer of coin-operated equipment in the United States. Seeberg’s efforts culminated in an expansion into the coin-operated amusement field in June 1964 through the purchase of Williams from Stern followed by the acquisition of United Manufacturing from founder Lyn Durant that September, which was absorbed into Williams. To run its amusement business, Seeburg kept on Stern as president of Williams after the purchase.

With the closing of Genco in 1959 followed by the purchase of Williams and United by Seeburg five years later, the fraternity of coin-op amusement manufactures dwindled to just five companies: Gottlieb, Williams, Bally, Chicago Coin, and Midway. Gottlieb remained the leader in pinball, a title it would not relinquish until the mid 1970s, trailed by Williams, Bally — back in the amusement pin business after bingo games were banned in the early 1960s — and Chicago Coin. In novelty, Williams continued to dominate pitch-and-bat baseball games and also took the lead in shuffle alleys and ball bowlers — which were often marketed under the United name — after Bally quit production at the beginning of the 1960s. Chicago Coin and Midway, meanwhile, offered the most comprehensive lineups of novelty arcade pieces. With so few manufacturers of equipment, however, stagnation quickly set in as new game designs became stale and predictable and companies often merely incorporating small cosmetic changes into existing concepts to differentiate them from the models released the year before. Just as coin-operated amusements appeared ready to enter a steep decline, however, a savior appeared in the form of a new type of arcade machine from Japan.

I’ve really been enjoying reading this series!

In your research, have you at any point come across the first arcade machine to tell the player Game Over when the game is finished? I’m not sure if it first appeared in pinball or shuffleboards, so I was curious if you’d come across anything.

Sorry to take so long to respond; I have been on the road. I am glad you are enjoying the blog. To answer your question, I have not come across the first “game over” message yet in my work, though I agree it would be interesting to know where it originated. If I learn anything, I will be sure to let you know.

Bally Bumper from 1936 had that very prominent light up message saying ‘game complete’. I reckon whoever coined the game over term might have taken it from there…

Another excellent post. I have really been enjoying this series. It’s one of the best short histories of the coin-op industry that I’ve ever read – though I think it’s going to run to over 100 pages so I don’t know it can really be called “short.”

I did notice, however, that you did not spend much time discussing Bally’s alleged mob ties – particularly the supposed involvement of Jerry Catena in the K.O.S. deal.

Is this because you’re planning to cover it later or in your book or do you feel that he evidence of his involvement (and Bally’s other ties organized crime) is unconvincing.

Thanks for the kind words Keith; they mean a lot coming from a researcher as excellent as yourself. As for Catena, I do plan to cover that whole mess, but I am saving it for the Atlantic City casino license affair. I believe that O’Donnell was a victim of circumstance, so desperate to save Bally that he did not look to closely at where the money was coming from. Klein, on the other hand, seems like he had some really shady friends. I see O’Donnell as a tragic figure and his K.O.S. Partners as slightly sinister.

Regarding your report on the Bally situation after 1962, you are way of base, when you go to the website that I told you to read my article at, you will find some interesting points regarding who was who, by the way, the Teamsters never financed Bally at all in the early day’s. Klien gave Jackie Presser some Bally shares for help in Vegas, also it was my late good friend Mickey Wichinsky that put Bally on the Map in Las Vegas, and also without my ex partner Cyril Shack in London, Bally may never have survived, but’s that’s another story, one thing ifs true, Billy O’Donnell was the real deal, and Si Redd was a bit of a phony as a person, I knew them all personally.

Freddy Bailey

Thanks for that. I’m sending you a longer email on some of these subjects, but I see now after checking my sources that I misread a confusingly worded article on the Teamster loans, which was actually referring to the Atlantic City casino operation in the late 1970s. I’ll remove that right away.

I’m interested in what you come up with on this and what confusing article you are referencing. The Boca Raton News article you referenced claims “Ultimately the partnership decided to borrow money from the Teamsters Central States Southeast and Southwest Areas Pension Fund to buy Bally’s Chicago building. The result was a $500,00 loan from the scandal-ridden fund on Oct. 5, 1964.”

The “partnership” included Klein, Green, O’Donnell, Kaye, and Jacobs (and, they claimed, Catena via his partnership in Runyon Sales).

If this partnership was K.O.S. then it seems that they did borrow money from the teamsters in 1964 (unless the article got it wrong). Or was this a different partnership.

The amount of detail and history in this series is overwhelming – in a good way! I’m working at a museum which possesses a Love Tester machine from the 70’s and I’ve been assigned the task of creating a display for it, so your posts have been extremely educational. I’ve saved a copy for our staff (with links and credits to you, of course) so they have reference material. Thanks for your help!

Came across this page searching history of my late stepdad Mike Balzano, who purchased Runyon’s telephone # for $40,000 from Jerry Catena in what year I am unsure. With what Mike called a turn key operation, then began the business with understanding from all the previous partners, on pinball row under the name Novel Vending. Mike told me Jerry Catena, Abe Green, and Irving Kay wanted to get out of their street businesses, at least what was on paper, to clean up their appearance for the Ballys Atlantic City venture. If this is already we’ll known amongst this group, I’m simply seeking clarity on my end.