Between 1895 and 1905, the penny arcade enjoyed a preeminent position in the entertainment world. Marcus Loew, who would later establish the Loews theater chain and forge MGM, ran an arcade, so did Adolph Zukor, who established Paramount Pictures, and William Fox, who gave his name to 20th Century Fox. The peep show dominated the arcade, and American Mutoscope dominated the peep show. But William Dickson and Henry Casler were never the type to rest on their laurels. In 1896, two years after completing the Mutoscope, Casler, at Dickson’s urging, developed the Biograph, a projector that allowed film to be displayed on a large screen rather than in a tiny wooden box. The Biograph was not the first film projector — the project was implemented to counter the Edison-backed Vitascope and the Lumière brothers were already making their first films for display via the Cinematograph in France — but American Mutoscope, renamed American Mutoscope and Biograph in 1899, was far better funded than most of its competitors and took an early lead in film projection. By 1908, three years after the first nickelodeon opened in Pittsburgh, D.W. Griffith was making short films for American Mutoscope and Biograph, and not long after that Mary Pickford and the Gish sisters were starring in them. Men like Zukor and Fox abandoned the arcade for the promise of the new motion picture business, and even American Mutoscope chose to distance itself from its roots, shortening its name to American Biograph in 1909. The penny arcade boom was over.

But coin-operated entertainment did not die. Just as the peep show fell out of favor, new advances in engineering resulted in the first practical fully automatic payout gambling machines. As popular as it was controversial, the advent of the “one-armed bandit” brought coin-op companies like Mills and Caille Brothers ever increasing profits and the industry an ever increasing stigma it would take decades to finally shed. As slot machines became increasingly regulated and pushed to the fringes of lawful society by the early 1920s, however, coin-op companies old and new began injecting a degree of skill into their games of chance. By the beginning of the 1930s, this trend culminated in three brothers developing a whole new arcade concept, the Sportland, which focused on games rather than novelty attractions or peep shows, signifying a paradigm shift within the industry.

NOTE: And here is part two of my six-part overview of the first hundred years of the coin-operated amusement industry. Principle sources this time around were Automatic Pleasures by Nic Costa, Arcade 1: Illustrated Historical Guide to Arcade Machines by Richard Bueschel and Steve Gronowski, Pinball 1: Illustrated Historical Guide to Pinball Machines by Richard Bueschel, the article “‘Sportlands’ Seen as Evolution of the Penny Arcade” in the April 1932 issue of Automatic Age, the article “The Fun Machines” in the July 4, 1977, issue of Sports Illustrated, and the article “Penny Arcade Philanthropist” in the October 16, 1948, edition of The New Yorker.

The Rise of the Slot Machine

A Sittman and Pitt five-reel poker machine, the precursor of the modern three-reel slot machine

Unlike the coin-operated amusement industry, which originated in Europe, the coin-operated gambling industry was a largely American phenomenon. This is because games of chance already had a long history in Europe before the advent of coin-operated machines, and consequently so did anti-gambling laws. In France, gaming for money had been prohibited by Louis XVI in 1781 by an edict that had survived the Revolution and the many governments that followed, while in England acts of Parliament passed in 1853 and 1854 severely limited the operation of automatic games of chance. Gambling games were still developed, of course, but the drop case games and allwins of Europe (briefly covered in a later post) were of an entirely different character than the machines that took over the United States, where gambling laws were fairly lax in the late nineteenth century, and the design of coin-operated gambling games flourished.

The earliest coin-operated gambling games were counter top models referred to as “trade stimulators” that usually sat on the bar of a tavern or next to the cash register at a store and gave a patron the chance to wager some of his spare change for the chance to win a prize such as a cigar or a piece of candy. The earliest known machine of this type was the Guessing Bank, developed by New Yorker Edward McLoughlin in 1876, in which inserting a coin would cause a dial to spin and stop on a random number. The patron would guess the number the dial would land on before inserting his penny and win a prize if he was correct. Like other coin-operated devices, however, the trade stimulator did not see wide distribution until the late 1880s. A variety of trade stimulators were developed in Europe during this period, but the spinning dial machine, which entered general use after British inventor Anthony Harris designed a wall-mounted version in 1889, remained the most popular. Before long, however, a new type of trade stimulator gave it a run for its money.

In 1890, Frank Smith of the Ideal Toy Company of Chicago introduced a new machine designed to automate the card game poker, which had first risen to popularity in the United States in the 1830s. Smith’s machine consisted of five reels that each featured a series of playing cards painted on them. When the patron inserted a coin, the reels would spin and each stop on a random card, which the patron hoped would result in a winning hand. If the player won a prize, he could collect it from an attendant. In 1893, the Brooklyn firm of Sittman and Pitt introduced its own card machine, which has been recognized as the first coin-operated gambling game to achieve national popularity in the United States.

By the middle of the 1890s, the trade stimulator had been joined by another type of coin-operated gambling device, the slot machine, which distinguished itself from other early gambling devices by featuring an automatic payout of a cash prize. The first slot machine was developed in Syracuse, New York, by John Lighton in 1892. In this machine, the coin inserted by the player would travel down one of two runways, either being deposited in the machine’s cash box or tripping a lever that caused two additional coins to be released and paid out to the player along with his original coin. In 1893, an inventor in San Francisco named Gustav Schultze combined the slot machine with the spinning dial concept in a device he called the Automatic Check Machine, in which the player pulled a lever on the side of the machine that caused a dial to spin atop a colored wheel. If the dial landed on a winning color, a bell would ring and two coins would be released to the player alongside a token with a random value between twenty-five cents and two dollars. Spinning dial slot machines became very popular over the next two years, but they were ultimately superseded by a new machine invented by a man named Charles Fey.

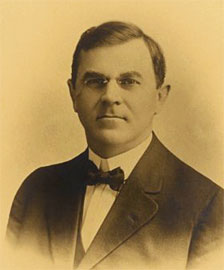

Charles Fey, developer of the first popular three-reel slot machine

Born in Vohringen, Bavaria, in 1862, Fey clashed with his father, a strict school master and an officer in a conservative church, so he left home at the age of fifteen to seek his fortune. After spending five years in London as an apprentice instrument maker at a shipyard, Fey saved enough money to immigrate to the United States. Arriving initially in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1882 and settling for a time in Wisconsin, Fey relocated to San Francisco in 1885 to serve as a model maker for California Electric Works. In 1894, Fey left the company with a fellow employee named Theodore Holtz to establish Holtz and Fey Electric Works to go into direct competition with their former employer. At the time, San Francisco was home to a large number of saloons — a legacy of the gold rush in the 1850s — and was also at the heart of the poker craze that had swept the United States, so the city became a major venue for the five-reel card machines just coming into vogue. Both Fey and Holtz became enamored with these new machines, but ultimately decided to part ways, with Holtz establishing his own company and Fey briefly going to work for slot machine pioneer Gustav Schultze before striking out on his own. Working in the basement of his apartment building, Fey designed his first gambling machine, called the Horseshoe, in 1894, and a second machine called the 4-11-44 in 1895, a form of lottery machine in which patrons lined up sets of numbers to win prizes. When these machines proved popular, Fey established Charles Fey and Company in 1896 to focus on the slot machine business.

Fey’s major breakthrough was to combine the two principle gambling attractions of the time: the slot machine and the card machine. Card machines were incredibly popular, but they could not automatically grant a reward, greatly decreasing their utility. Early slot machines could provide a payout, but lacked the excitement of the card games. Fey therefore decided to add an automatic payout mechanism to the five-reel poker machine, but the mechanical challenge proved too difficult. Fey’s solution was to pare down the number of reels on his machine to three. Originally manufactured as the Card Bell sometime between 1898 and 1905, Fey quickly decided to replace the pictures of cards on the reels with images like stars and bells since the player was no longer attempting to complete a poker hand and changed the name to the Liberty Bell. The combination of spinning reels and automatic payout proved irresistible, and the Liberty Bell soon became a sensation in the San Francisco area. The machine did not spread beyond the city, however, as Fey had no desire to mass produce and sell his invention, instead making deals with bar owners to install slots for a fifty percent take of the coin drop. This situation persisted until the disastrous 1906 San Francisco earthquake, during which Fey’s workshop burned to the ground. This loss left a vacuum in the three-reel slot machine business that was quickly filled by the Mills Novelty Company.

As discussed previously, Mills released its first slot machine in 1897, a spinning dial machine called the Owl, one of the earliest models designed to stand on the floor rather than on a counter top. Two years later, a New York manufacturer named Mathias Larkin created a similar machine called the Admiral that was the first slot machine to be advertised nationally and featured an image of Admiral George Dewey, extremely popular after his victories in the Spanish-American War, to help spur sales. Impressed with Larkin’s work, Herbert Mills hired him to open a San Francisco office and serve as his company’s promotional manager. It was no doubt through this branch office that Mills first became aware of Fey’s Liberty Bell. What happened next between Fey and Mills differs based on who tells the tale. Fey and his descendants claim that Larkin took one of Fey’s machines from a local tavern so that Mills could copy and steal the design. The Mills family, on the other hand, states that Fey came to Chicago and offered to turn the design over to Mills in return for receiving the first fifty machines off the assembly line at no cost. As Fey lost the ability to build his own machines in the earthquake and Mills already had a history of buying up the rights to products from other inventors, the Mills version feels more plausible. Either way, the Mills Liberty Bell entered mass production in 1907.

The Mills Bell Machine, which brought the three-reel slot machine to prominence

With the Liberty Bell finally becoming available nationwide, the popularity of three-reel slot machines soared, completely displacing the earlier dial machines and leading the larger manufacturers in the coin-operated amusement business to concentrate almost exclusively on slots. Taking advantage of its head start over the competition, Mills built a commanding lead in the market that would last until the early 1960s. Caille Brothers also quickly embraced the “one-armed bandit” and competed closely with Mills until the end of World War I, when the Detroit company began to fall behind. Mills’ closest competitor thereafter was a manufacturer named Ode Jennings. Born in Kentucky, Jennings entered the coin-op business by moving to Chicago in 1901 to become a salesmen of penny-arcade machines and first gained notoriety through managing the Mills arcade at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. In 1907, he established the Industry Novelty Company in Chicago to deal in used slot machines, vending machines, and scales, which he would often modify with features of his own design. Industry began manufacturing its own slot machines in 1911 and changed its name to O.D. Jennings and Company in 1928. With Mills, Jennings, and more distant competitor Watling all based out of Chicago, the Windy City became the center of the coin-operated gambling and amusement industries by the late 1920s.

As slot machines continued to grow in popularity throughout the first decade of the twentieth century, a backlash began to develop against the machines, which were seen in many circles as nothing more than a way for shopkeepers and saloon owners to cheat honest patrons out of their money. As a result, San Francisco, the original center of the industry, banned slot machines that dispensed a cash payout in 1909, and the entire state of California followed suit two years later. This signaled the beginning of a series of widespread bans that soon left slot machines illegal in most of the country. The beginnings of Prohibition in 1920 further stigmatized the slot machine, as speakeasies that were engaged in illegal activities anyway often included the devices on their premises and the cash-only nature of the business quickly attracted organized crime. Manufacturers were also hit hard by the onset of Prohibition, as bars and saloons had been the primary venue for slot machines, and the closing of these establishments left a hole that other businesses could not entirely fill. While the slot machine industry attempted to compensate for these setbacks by producing machines that awarded prizes of candy and gum instead of money, shops that operated slot machines faced the constant threat of confiscation and other legal action. With slot machines and trade stimulators under attack and pushed to the outer margins of the law by the mid-1920s, several entrepreneurs began emphasizing skill-based elements in their products so they could argue the machines were not purely games of chance. This move ultimately helped revive the penny arcade.

Coin-Op Amusements Make a Comeback

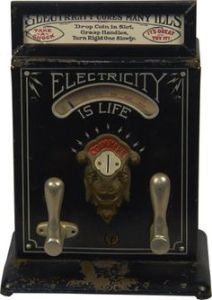

An Exhibit Supply True Love Letter card vendor

The 1910s were a hard decade for the coin-operated amusement business. With the rising popularity of the cinema and the far cheaper production costs of film projection versus peep shows, American Mutoscope and Biograph halted all production of both Mutoscope machines and films in 1906. With the Mutoscope overthrown, arcades had to rely more on their novelty pieces like testers and shockers to draw clientele, but there were only so many ways to build a strength machine or a scale, so without the attraction of new peep shows, there was little reason to come to the penny arcade — unless you were looking for one of the racier films in a seedier location. World War I and Prohibition killed off most of what remained of the business, the former curtailing the development of new machines and the latter closing the bars that had been the prime venue for testers even before they incorporated coin control. The smaller companies in the arcade business could not survive the temporary halt of new machine design brought on by the war, and most of them went out of business. While the larger companies survived, they also abandoned the dwindling arcade scene. Rosenfield Manufacturing left the coin-op business entirely to create electrical appliances like vacuum cleaners, while Caille Brothers turned its entire focus to slot machines after Arthur Caille died in 1919, as Adolph Caille had never really liked the arcade business in the first place. In 1929, Caille began building outboard motors alongside its coin-op production, and in 1937 Adolph Caille sold the firm to a rival motor manufacturer. Only Mills continued to offer a full line of arcade equipment, but it also now focused on slot machines and did not create new arcade pieces, merely continuing to sell its existing line. Just as everyone else was abandoning the arcade, however, one man decided the time was ripe to move in.

John Frank Meyer was born in Peoria, Illinois, in 1881. Entering the printer’s trade, he established his own small printing shop in Chicago before joining a firm called the Exhibit Supply Company in 1907 as a partner. Organized in 1901 as a postcard printer, Exhibit expanded its line rapidly after Meyer joined to become the largest supplier of printed cards for fortune tellers, horoscope machines, and all the other types of card vendors found in the penny arcade. Meyer took full control of Exhibit in 1910 and moved the firm into building its own card vendors in 1914. As the penny arcade approached the nadir of its decline, it actually became a somewhat fashionable spot for young couples to have a risque night out viewing lewd peep shows and purchasing printed love letters from card vendors as souvenirs. By 1917, partially aided by soldiers flocking to city night life to take their girls out one last time before shipping off “over there,” Exhibit card vendors enjoyed enormous popularity and became a key component of the shrinking penny arcade business. After World War I, Meyer decided to introduce a full line of arcade machines and hired Perc Smith, a former production manager for the Meade Bicycle Company and salesman for Mills Novelty with strong credentials in manufacturing, sales, and arcade operation, to sell them. Together, Meyer and Smith built Exhibit Supply into the most important arcade equipment manufacturer of the 1920s.

While the marginalization of the penny arcade and the closing of the bars seriously wounded the industry, companies like Exhibit continued to hang on by transforming the nature of the business. The increasing popularity of the automobile after the introduction of the Ford Model T in 1908 ultimately led the Federal Government to pass the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 to connect much if the United States by road. Whereas in the past coin-op sales to smaller towns and rural areas had been factory direct and limited to a small number of saloons and hotels that would pick up their machines at the local train station, the rise of pickup truck delivery services opened up a wider array of small locations like grocery stores, restaurants, barbershops, and candy stores to coin-operated amusements. By the mid-1920s, this led to a development of a new middleman in the coin-operated amusement business, the regional distributor, who would order machines from several manufacturers in large volume and sell them to operators that would maintain machines in multiple locations along a truck delivery route. The operator would be responsible for keeping these machines in good repair and would split the coin drop with the owners of each location along the route to recoup the purchase price. This manufacturer-distributor-operator model of selling coin-operated amusements would persist for decades.

Just as the coin-operated amusement industry was extending its reach into new areas through regional distribution, the increased regulation of the slot machine and trade stimulator lured a variety of new players to the market that were eager to keep the coin-operated gambling industry alive through injecting a degree of skill into their games of chance. One of the first manifestations of this trend was the counter top gun game, in which the player would generally insert a coin into a slot that served as a bullet that the player would attempt to shoot into a scoring hole at the back of a glass-covered playfield in order to win a prize. In the early days of the industry, this would be a cash prize, but as gambling devices came under greater scrutiny, this was usually changed to candy in an attempt to avoid confiscation. While this type of trade stimulator dates back to a model created by Englishmen David Johnston in 1889 and achieved popularity in the 1890s, it did not become an arcade mainstay until a man named Walter Tratsch introduced his version to the industry.

Target Skill by A.B.T. Manufacturing, one of the first popular skill-based coin-operated amusements of the 1920s

Tratsch’s association with the coin-op industry began in 1902 when he joined with Frank Mills, a brother of the founder of the Mills Novelty Company and the man in charge of its East Coast operations, to run a penny arcade in Hoboken, New Jersey. Like slot machine manufacturer Ode Jennings, Tratsch operated arcade machines at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, and he also partnered with Mills to run Owl and Admiral slot machines in the years before his company began mass-producing the Liberty Bell. After operating machines in Panama and Argentina starting in 1908, Tratsch came to Chicago in 1910 to open his first plant, which specialized in machine repair and parts fabrication for the coin-op industry. A trip out West to partner with Charles Fey followed in 1913 before he returned East in 1915 to partner with an acquaintance first met when they were both running coin-op machines at the St. Louis World’s Fair named Jack Bechtol, with whom he established the Diamond Confection Company and the Southern Confection Company in South Carolina to operate coin-op routes in the South. In 1919 the duo established a new company in Memphis that morphed into the A.B.T. Manufacturing Company when another long-time friend of Tratsch named Gus Adler invested in 1921. The company was named by combining the initials of the three owners, though Adler sold out his interest to a Chicago financier named Bill Gray two years later. This company perhaps made its biggest mark on the industry through the introduction of an early coin chute, which required a coin to travel down a ramp before activating a machine and therefore made slugging much more difficult.

In 1925, A.B.T. relocated to Chicago and debuted one of the most important coin-operated machines of the 1920s, a countertop pistol game called Target Skill. Like earlier gun trade stimulators, Target Skill featured a glass-protected target area housed within a wooden cabinet, but unlike these earlier machines, the game provided five small steel balls as ammunition for the cost of a penny. The objective was to shoot these balls into five target holes of decreasing size, with each direct hit causing a flag to drop over the target. Unlike slot machines, there was no payout mechanism attached to the machine, making it a pure game of skill free of the legal challenges and confiscation hassles plauging most countertop devices. An instant success, Target Skill games were soon being produced at a rate of 2,000 a month as sales reached 40,000 units within a decade. Once the popularity of the game was well established, A.B.T began releasing variants that featured different playfield configurations and/or more prominent payout elements. These included the popular Big Game Hunter, in which a successful hit on one of the three targets would cause a slot machine reel to spin and lining up the proper targets would allow the player to obtain prizes such as a small cash payout or a pack of cigarettes from the operator, and the Challenger, which provided ten shots for nine scoring holes. A.B.T. continued to sell variations on Target Skill until the early 1960s and manufactured over 300,000 of them during that time. As one of the earliest coin-operated products to gain widespread popularity by focusing primarily on player hand/eye coordination and skill rather than on strength/endurance testing, vending, or random chance, Target Skill represented one of the first attempts to move coin-operated products from novelties and gambling concepts to actual games, paving the way for a major paradigm shift in an arcade industry that had remained stagnant for nearly two decades.

The Erie Digger, which launched the first crane game boom

A second concept particularly important to reviving the arcade was the coin-operated digger, or crane, machine, which like the new target shooting games combined elements of both skill and chance. Sources differ on when exactly the first digger machines entered the marketplace, but most evidence points to the first models appearing in 1924. In that year, Norwat Amusement Devices introduced the Steam Shovel, while the Erie Manufacturing Company began selling its Erie Digger, which dominated the market into the early 1930s. By 1926, digging machines had become standard fare at boardwalks and amusement parks, but were particularly attractive for traveling carnivals due to their compact size and relative simplicity. In fact, it was a carnival concessions operator named William Bartlett who introduced the next important advance in crane games in 1926 with his popular Miami Digger, which allowed the patron to move the crane all around the inside of the box rather than just up and down as in earlier models. Unlike Erie, Bartlett did not mass produce and sell his machines, but instead dispatched licensed agents to travelling carnivals around the United States and Canada, who would operate banks of 12-17 units on his behalf. By the time Bartlett died in 1948, over forty operators were supplying cranes to all the major carnivals in North America. While crane machines only vended candy at first, it did not take long for operators to offer silver dollars, paper currency, and bundles of coins wrapped in cellophane as prizes instead.

With the success of Target Skill and the carnival diggers, an array of new coin-operated games appeared in the late 1920s. Exhibit Supply remained in the forefront of the market by readily embracing new machine concepts. These included a popular crane game called the Iron Claw that debuted in 1927 and a target shooting game called Automatic Pistol Range launched in 1929 in which one or two players shot at targets mounted on a motorized carriage that rolled across a playfield housed in a large wooden cabinet. Even Mills released a new punching bag strength tester in 1926. Perhaps the most surprising return of the decade, however, was the Mutoscope, brought back by a businessman named William Rabkin.

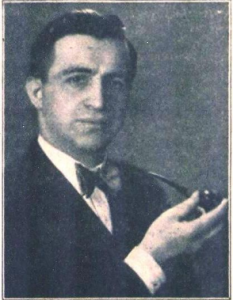

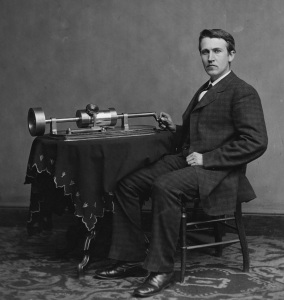

William Rabkin, the founder of International Mutoscope

Born in 1894 in Babruysk, then part of Russia now part of Belarus, Welvel Rabkin — clerks at Ellis Island made him a William — entered a trade school at the age of twelve and spent three years learning how to be a machinist. Rabkin’s father ran a modestly successful wholesale farm produce business until a warehouse fire bankrupted him, and he immigrated to the United States to work as a garment presser in New York City. After becoming established there, he sent for the rest of his family, who joined him in 1909. After stints as a plumbers apprentice and electrician’s helper, Rabkin finally found work in a machinist shop. Several years later, he and a partner established their own shop. After a falling out, however, Rabkin sold his interest in the shop and looked for another business involving machines. This quest led him to American Biograph and the Mutoscope in 1920.

Once a leader in the film industry, Biograph fell on hard times in the 1910s. In 1908, the company joined with Edison to form a trust called the Motion Picture Patents Company that dominated film distribution and limited production to a small number of allied studios, but the Federal Government broke up the firm in 1915. In the meantime, Biograph had declined to enter the new feature film business due to the expense involved, causing Griffith to leave with most of the company’s stars. Now that feature films were taking off, Biograph lagged the competition and could no longer rely on its monopoly to stay relevant. The company released its last short film in 1916 and thereafter relied on reissues of its old films to barely stay afloat. For this reason, the company was more than happy to sell Rabkin its entire stock of Mutoscope machines and films.

American Mutoscope had never sold its peep shows, instead licensing the machines and the films to play in them to penny arcades. Rabkin decided that in order to turn a profit, he would have to sell his wares instead, but there was little interest among arcade operators due to a lack of new content. Rabkin therefore commenced production of new short films in 1924, creating roughly five hundred reels in a variety of genres before shutting down production again in 1933. Sales remained sluggish, however, until 1926, when the Mutoscope suddenly became fashionable again in Britain. As sales took off overseas, Rabkin’s business grew rapidly, and he was able to combine his experience as a machinist with a new influx of capital to expand his arcade offerings beyond the peep show business.

The first original machine International Mutoscope created was the Shootoscope, a countertop target shooting trade stimulator released in 1926. Like other games in the genre, play consisted of inserting a penny into a coin slot, which the player then fired at a target housed in a glass-covered wooden case. If the player’s coin hit the whole in the center of the target, it would be returned to the player. Next, Rabkin developed his take on the classic fortune telling machine — marketed as Grandmother’s Predictions — which debuted in 1928. Both machines remained popular for years, but Rabkin experienced his greatest success through the newly emerging crane games.

During his lifetime, William Rabkin claimed to have invented the coin-operated digger after taking inspiration from watching a steam shovel dig out the foundation of a building while he was still working as a young machinist shortly after coming to the United States. In truth, by the time Rabkin developed his Electric Travelling Crane in 1928, diggers had already been a popular attraction for several years, and he likely just adapted machines that he had already seen at carnivals and arcades. Indeed, the Exhibit Supply Company thought Rabkin’s crane was so similar to its own Iron Claw, that it sued International Mutoscope for patent infringement. Regardless of the source, Rabkin continued to improve his device over the next several years, and by 1933 the Travelling Crane had played a crucial role in igniting a digger boom that swept across the United States and Europe. Before long, crane games housed in elaborate art deco cabinets could be found not only in penny arcades and carnivals, but also in department stores and hotel lobbies. There were even so-called “craneland” arcades that housed nothing but digger machines. By 1936, Rabkin had sold over 25,000 diggers, a significant number for a large arcade piece of the era.

While cranes, gun games, and card vendors began enjoying increasing popularity in the mid 1920s, the venues for these games remained relatively limited at first due to the continued sluggishness of the penny arcade business. Arcades were still associated primarily with peep shows and novelties in this time period, and the appeal of these machines had waned years before. Even with International Mutoscope now releasing improved viewers and new reels, interest in the peep show remained relatively muted in the United States. A new paradigm in arcade entertainment was desperately needed, and it was finally provided by the Chester-Pollard Amusement Company.

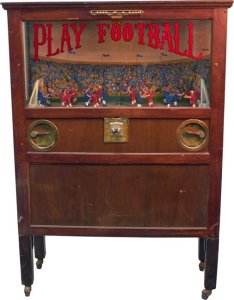

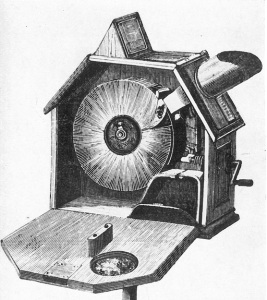

The Chester-Pollard Play Football game, which brought competitive sports games to prominence in the arcade

The three Chester brothers — Pollard was their mother’s maiden name — entered the amusement industry in the early 1920s with a fortune telling machine. Frank Chester, an electrical engineer, was the visionary behind the company, while Charles was an expert in mechanical technology, and Ernest was a consummate businessman. In 1926, a British manufacturer named Freddy Bolland called on Chester-Pollard in New York to see if the brothers might be interested in the North American manufacturing rights to a manikin football game for which he owned the patents. In this game, housed in a large wooden cabinet, two players would control the sides of a football match by pressing a lever to cause all the players to kick their legs at once. For a nickel, the players would get a single ball and would have to time their kicks to score a goal on their opponent. Score could be kept using a set of beads strung along the top of the cabinet, but every time a goal was scored, a new nickel would have to be inserted to keep playing. Chester-Pollard agreed to take on the product, built 100 units, and tested them at select locations over the course of a year. Proving itself a huge moneymaker, it was released generally in 1927. Next came a mannikin golf game, which despite a relatively steep price of $150 for the penny model and $175 for the nickel model sold over 7,000 units. In 1929, a horse racing game called Play the Derby debuted, in which two players turned cranks to drive horses around a track, and became yet another hit. Chester-Pollard games were soon appearing in thousands of hotels, clubs, and railroad depots and could even be found on steamship lines.

With their competitive sports games doing so well, the Chester Brothers decided to expand into sports tables that did not incorporate coin control. Baseball, table tennis, hockey, and bagatelle tables were tested in exclusive locations such as the Lido and Westchester-Biltmore Country Clubs, where they proved a tremendous success. Based on these results, the Chesters believed they could pioneer a new arcade concept based around table games and exercise machines with and without coin control. They named this new concept the Sportland.

In 1930, Chester-Pollard began testing the Sportland concept in existing arcades such as Playland Park in Rye, New York, owned by William Rabkin of International Mutoscope. When these locations proved successful, they opened a purpose-designed Sportland in an outlying district of Brooklyn. In its standard configuration, the Sportland featured a small array of coin-operated machines such as gun games or diggers in the front of the establishment and a large table game area in the rear blocked off by a fence. For a quarter, a patron could spend thirty minutes playing all the table sports games they wanted. The old penny arcade had failed when the public grew tired of peep shows because they had to be situated in a major thoroughfare to attract volume patronage, but owners could no longer afford the correspondingly high rents. Sportlands, on the other hand, quickly attracted patrons whether they were located on a major street or not, and by the summer of 1931 they were a sensation throughout the New York area.

The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 cemented the arcade revival. With worsening economic conditions severely restricting the amount of money most Americans could afford to spend on leisure in the early 1930s, arcade machines that could be played for just a nickel or even a penny became one of the few affordable activities in the country, causing revenues from coin-operated amusements to skyrocket. In 1930, over 250 companies manufactured 250,000 units of over 400 different games, and by 1934 these manufacturers were taking in more than $10 million annually. Meanwhile, Chester-Pollard had established fifty-two Sportland arcades in the New York City area alone by 1933, and they became a model for entrepreneurs all over the nation. Consequently, the arcade completed its transition from a novelty attraction to a venue for games of skill, taking on the basic form it would maintain for the next sixty years. Before long, many arcades were taking in over $800 worth of pennies and nickels a week, while prime locations could pull in as much as $1,200 a week despite an ever-worsening economy. Gun games, competitive sports games, and diggers all played their part in this renaissance, but the most important contributor by far was a relatively new amusement called pinball.