This post is part of an ongoing series annotating my book They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies That Shaped the Video Game Industry, Vol. I. It covers material found in chapter 4 on pages 43-59. It is not necessary to have read the book to comprehend and appreciate the post.

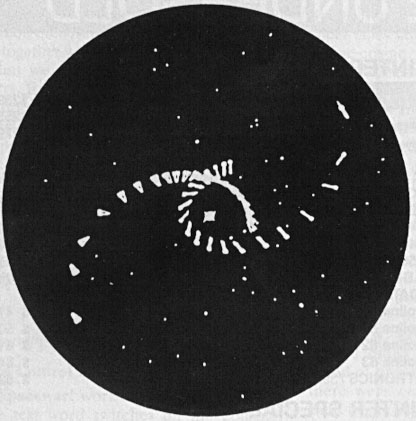

After three chapters depicting a motley assortment of AI experiments, military simulations, and demonstration programs, chapter four finally arrives at the inflection point for the birth of commercial video games: the creation and proliferation of Spacewar!, conceived by Steve Russell, Martin Graetz, and Wayne Wiitanen and largely programmed by Russell with support from Graetz, Peter Samson, Dan Edwards, Alan Kotok, and other hackers hanging around the PDP-1 at MIT. While Spacewar! itself was not commercialized in its original incarnation, its direct influence on the first commercially released video game, Computer Space, and the first significant video game company, Atari, give it pride of place in any history of the video game industry. While the book already discusses the creation of the game, this annotation will explore what we know of the chronology of the game’s creation in a little more detail.

Before the last few years, there were three significant sources discussing the birth of Spacewar! The first was an article written by famed Whole Earth Catalog creator Stewart Brand for Rolling Stone and published in October 1972. While the intersection of computers and counterculture is somewhat overblown in some monographs discussing the early days of personal computing, there was significant collision between these two forces in the San Francisco Bay Area and the adjacent Santa Clara Valley, where the summer of love and the free speech movement mingled with the prestigious technical degree programs at UC Berkeley and Stanford. Brand himself was Stanford educated and embraced the counterculture values of individual empowerment as a tool for social justice and ecological renewal. The Whole Earth Catalog was one aspect of this empowerment drive, a how-to guide and catalog of useful items for self-sufficient living off the land, which was a key tenet of the commune movement.

For Brand, liberating the individual from the shackles of modern society was about more than farming and communal living; he also felt it important to expand the mind. An associate of Ken Kesey, Brand experimented with LSD and other mind-altering drugs in the 1960s as one means to this end, but by the 1970s he became convinced computers possessed even more potent mind-altering powers. To Brand, learning to use a computer was another path towards taking control of one’s own destiny, and nothing showcased the power of a computer like a game. As he put it in a 2016 retrospective about his 1972 article: “I saw them having some kind of out-of-body experience. Their brains and their fingers were fully engaged. There was an athletic exuberance to their joyous mutual slaying. I’d never seen anything like that.” Of course, he was referring to people playing Spacewar!

By 1972, Spacewar! had become so enmeshed in university electrical engineering and computer science departments, government think tanks, and corporate research facilities that no less a personage than Alan Kay, then at Xerox PARC, opined that “The game of Spacewar blossoms spontaneously wherever there is a graphics display connected to a computer.” The game certainly did not escape the notice of Brand, who encountered it again and again as he toured computing centers in the Bay Area to come to grips with this exciting new technology. In 2016, he still remembered his enthusiasm: “I was intrigued at the quality of game design intelligence these guys had from the very start. You were balancing skill versus luck, and not only dealing with the threat of your opponents, but the threat of losing control and being slurped into the sun. And hyperspace was an astonishingly brilliant breakthrough.”

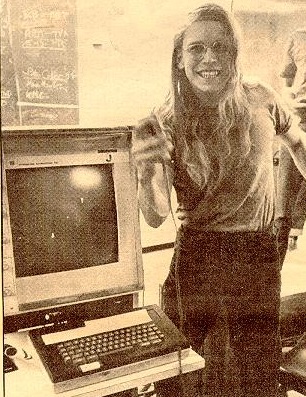

Brand’s love of the design for Spacewar! echoed his larger appreciation for hacker culture, which brought the same do-it-yourself mentality of the commune to the computer lab. He became determined to document the hacker movement for the general public using Rolling Stone as his vessel, and he chose Spacewar! as his — and the reader’s — entrée into the hacker world. He convinced Lester Earnest, the manager of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (SAIL), to shut down the premises for an evening to hold a competition he dubbed the “Intergalactic Spacewar Olympics” in which an assortment of students and researchers faced off in a multiplayer variant of the game that had recently been created by Ralph Gorin. After a series of 2v2 preliminary matches, a final five-player free-for-all determined the champion. Brand and photographer Anne Leibowitz were on hand to capture all the action, including the triumphant winner of the affair, Bruce Baumgart, standing next to a terminal with a huge grin on his face as he celebrated his victory.

While Brand focused most of his article on what may have been the first esports competition, he did spare a few paragraphs for the creation of the game, complete with quotes from Steve Russell. Brand captured the barebones story that Russell created the game in 1961-62 at MIT on a PDP-1 after being inspired by E.E. Smith’s Lensman novels, that Peter Samson added the “Expensive Planetarium,” and that Dan Edwards and Alan Kotok also pitched in, but he missed the equally important contributions of Graetz and Wiitanen to the whole affair. That would have to wait for the August 1981 issue of Creative Computing, in which Martin Graetz himself took a stab at detailing the origin of the game.

Of all Spacewar!‘s many fathers, Graetz was the most literary minded, having been an avid reader and writer of science fiction since his secondary school days and even managing to have a story published in a pulp magazine at one point. Therefore, he took on the mantle of semi-official Spacewar! historian. As Graetz revealed to me, he was an employee at DEC when company co-founder Ken Olsen set up a small company museum featuring a few old computer systems that soon after moved to a public exhibition space in Malboro, MA, and served as the genesis of what is now the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. Graetz helped restore one of the few surviving PDP-1 computers for the museum and made sure Spacewar! ran on it. He also contacted David Ahl at Creative Computing and pitched the idea of doing an article on the history of the game to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of its inception in 1981. Ahl loved the idea and commissioned the article.

In “The Origin of Spacewar,” Graetz gave the first complete telling of the Spacewar! story, which he based not only on his own recollections, but also on the memories of his fellow hackers and several of MIT’s computer custodians like Jack Dennis and John McKenzie. Here we learned for the first time of the “Hingham Institute” consisting of Graetz, Russell, and Wayne Wiitanen, roommates and co-workers at Harvard’s Littaeur Statistical Laboratory who were reading E.E. Smith novels and watching special-effects-laden b-movies out of Japan from Toho Studios. As Graetz tells it, he moved on from Harvard to take a job with Jack Dennis at MIT in summer 1961, at which point he learned DEC would be donating a shiny new PDP-1 computer to the university in the fall. Wowed by the graphical demo programs already extant on the forerunner to the PDP-1, the prototypical TX-0 housed in MIT’s Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE), he convened the Hingham Institute to do them one better.

In Graetz’s telling, Wiitanen becomes the real hero:

With the Fenachrone hot on our ion track, Wayne said, “Look, you need action and you need some kind of skill level. It should be a game where you have to control things moving around on the scope, like, oh, spaceships. Something like an explorer game, or a race or contest…a fight, maybe?”

“SPACEWAR!” shouted Slug and I, as the last force screen flared into the violet and went down.

With that, Graetz informs us that Russell returns to MIT from Harvard, tells everyone about this neat demo idea, and finally gets to work on the game after Alan Kotok provides some sine-cosine routines directly from DEC that imploded the last major excuse Russell had been clinging to so he did not actually have to put in the work. Then Samson adds his starfield, Dan Edwards is given credit for bringing gravity to the match, Graetz himself programs a hyperspace feature, and Kotok and Bob Saunders, members of some organization briefly identified as the Tech Model Railroad Club, create some custom control boxes to make it all much easier to play. By an MIT open house in May, Spacewar! is done and makes its public debut.

Those wanting further insight into this “Tech Model Railroad Club” (TMRC) would have to wait three more years when the third and final significant source on the creation of Spacewar! was published: Steven Levy’s Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Taking up where Brand left off, the book attempts to chronicle the birth and spread of hacker culture from the insular nerds at MIT to the more open counterculture crowd in the San Francisco Bay Area, and finally to the business-minded hackers like Ken Williams and Doug Carlston who established the computer game industry. While his version of the creation story largely follows Brand and Graetz, he spends considerable time fleshing out the history and motivations of the TMRC hackers and provides profiles on some of the supporting characters in the Spacewar! story like Samson, Kotok, and Saunders. While Kotok and Samson in particular are elevated in this account, Graetz and Wiitanen fade once again into the background, presumably because they were never really part of the TMRC hacker scene that Levy is so eager to chronicle. While the text indicates an awareness of the Hingham Institute, Levy joins Brand in focusing Russell as the key figure in not just programming the game, but also in conceiving it.

Hackers and “The Origin of Spacewar” defined the Spacewar! story in the historical record for the next thirty years. Steve Bloom’s Video Invaders, which predates Hackers, essentially regurgitates the Creative Computing story that had just come out the year before. Steven Kent’s Ultimate History of Video Games cribs from Hackers, supplemented by Kent’s own interview of Russell. As is typical, however, Kent cannot help but introduce a tiny error in the narrative when he refers to Russell’s love of “Doc Savage” stories when other sources clearly demonstrate this should have been a reference to the Lensman books written by Doc Smith. Rusel Demaria and Johnny Wilson return to the Creative Computing story in High Score as befits their own close affiliation with early computer magazines, while Tristan Donovan’s Replay hews closest to Hackers with its emphasis on Russell and his place in the larger TMRC hacking scene.

While the Brand, Graetz, and Levy renditions of the origin of Spacewar! place their emphasis on different people, they largely agree on chronology. In this tale, word of the PDP-1’s imminent arrival comes in the summer of 1961, the computer arrives in the fall, and Steve Russell finally gets to work on the game in December. In early 1962 other programmers like Samson and Edwards add a host of new features like an accurate starfield and gravity, and the whole affair is wrapped up in time for an MIT Open House in May. This general account, based entirely on the memories of the participants anywhere from ten to twenty years after the fact, appears to be generally correct, but as more documentary evidence has become available in the past few years, this timeline has been tweaked.

The first breakthrough in cracking open the Spacewar! chronology came from Austrian web developer Norbert Landsteiner. Around 1996, Landsteiner became a pioneer in Java game programming, releasing takes on several classic arcade games like Space Invaders and Pac-Man that could be played within a browser. In the early 2010s, he began collecting paper tape and original code of Spacewar! variants to recreate them on his website, and managed to get his hands on some of the earliest extant code for the game. In particular, he made the remarkable discovery of Spacewar 2B, which is now the earliest known “complete” version of the game, i.e. the version that appears to have all the pieces present at the reputed public debut of the game in May 1962. Two versions were discovered, one dated March 25, 1962 pulled off an original paper tape, and one dated April 2, 1962 reconstructed from .bin files. The two versions are largely identical save for a few minor settings parameters. These files show that the renderings of the ships, the basic controls, the gravity of the sun, and the starfield were all implemented as of March 25. They further give an exact date for the integration of Samson’s Expensive Planetarium, patched in according to the comments on March 13, 1962. There is also a space carved out to “put [in] more bells and whisles [sic], like hyperspace,” but the functionality is not actually present. Landsteiner did also discover the separate hyperspace patch in a version dated May 2, 1962.

Landsteiner’s work has been invaluable for determining when the original version of Spacewar! reached a finished state, but it did little to enhance or corroborate the narrative around when the game was conceived and when programming began. Narrowing down the first point is where my own work took center stage. In 2015, I tracked down Wayne Wiitanen on the Internet and emailed him several questions that he was kind enough to answer. To my knowledge, this was his first contribution to the historical record outside his uncited contributions to the Graetz article, though he has given at least two interviews since. I had little hope he would be able narrow the timeline much after over fifty years, but I was proven wrong. As Wiitanen explained it: “It had to be summer, but before August 10th (the date when my recall orders issued) as I had to report to Ft. Bragg in October and didn’t have time to get involved in detailed design or programming.” So while we still don’t know exactly when in the summer the brainstorming session occurred, we do know it happened before August 10th, a hard date fixed by Wayne’s recall orders. This matches up with the recollections of both Graetz in his article and Alan Kotok in Hackers that the MIT community became aware of the impending computer donation at that time.

So when did Russell’s work on the game actually begin? Russell himself in a 2008 oral history with the Computer History Museum remembers the development environment, including display, being in place by fall 1961 and development beginning before the end of the year. Hackers further pinpoints the date to early December 1961. Graetz states “Slug produced the first object-in-motion program in January 1962,” which does not explicitly contradict the early December start date, but does cast it into serious doubt. Graetz also makes another curious claim that no other person, in articles or oral histories, has ever made, which is that the display “was scheduled to be installed a couple of months after the computer itself.”

This remained the state of our knowledge on the matter until 2017, when fellow researcher and frequent collaborator Ethan Johnson made one of his trips to the National Archives facility in Chicago. This facility is home to much of the original Magnavox patent suit, which was adjudicated in federal court in Chicago. As discussed previously, the defense to this lawsuit resolved around invalidating the Baer and Rusch patents through proving the existence of “prior art” in video games, which naturally made Spacewar! one of the focal points of the trial. Representing MIT in this case was John McKenzie, the engineer charged with keeping the TX-0 and PDP-1 in working order at the time of the events in question. Mr. McKenzie’s deposition in the case, taken in 1975, was still extant in the court records when Ethan pulled the files. Not only did McKenzie testify to his own personal knowledge of events, but he also brought with him the log books for the PDP-1. As time on the computer had to be signed out, this meant that he had with him a complete written record of who did what with the computer throughout 1961 and 1962!

The main dates McKenzie’s testimony firmly establish are the dates both the computer and its display were delivered. According to the logs, the computer arrived September 15, 1961, and the monitor was installed on December 29, 1961. So Graetz was right: the monitor really was installed a few months after the fact! This calls into question large portions of Russell’s recollections, namely that he was partially inspired to finally start creating the game by the so-called “Minskytron” graphical demo program and that he started coding the game in 1961. The Minskytron could not have existed before Marvin Minsky had a display to actually program, and Russell himself is unlikely to have begun programming in December without a display to work with. This appears to confirm the Graetz account that programming on the game commenced in January 1962.

Later on, McKenzie provides another gem:

McKenzie: On page 8, the middle of the page, it says “Monday 19 March 1962. Clock equals 2694. 7.” Some more beyond that, at 0345, “Power off. installed user’s IOT input to I/0 on IOT11.” That was initialed RAS, which would have been Robert Saunders.

[…]

Q: Does that entry have a meaning to you?

McKenzie: Yes; very significant. The students built up two control boxes; and at this time the control, some became optional with a sense switch setting, determining whether you wanted to take input from the earlier mentioned test word switches or from the control boxes. These control boxes, the state of the switches in the control boxes was, the term — the computer term is strobed or brought into the computer on the execution of an IOT11.

So thanks to McKenzie’s meticulous record keeping, we know the custom control boxes were installed on March 19! Note the installation was done by Bob Saunders. In “The Origin of Spacewar” Graetz credits the boxes to both Saunders and Kotok, but in a 2018 oral history with the Smithsonian, Saunders took sole credit for developing the boxes. The log book does not necessarily corroborate Saunders’ version of events, but it does provide support for the idea that at the very least he took the lead on this project even if Kotok helped him scrounge up some parts.

McKenzie also remarks on another aspect of the game’s creation that has nothing to do with chronology, but is worth mentioning here. In describing the people behind Spacewar!, McKenzie says:

Some of the people who were most involved would have been Peter Samson, Daniel Edwards, Alan Kotok. Steven Russell I did not see as frequently. He was a Harvard student, and was not around during the day. I knew of him, I had met him; but not frequently.

Note he identifies Russell as being affiliated with Harvard. He was not a student — that’s a provable error — but this contradicts Graetz’s assertion that Russell had returned to MIT at the time he created Spacewar!. McKenzie’s testimony is not the only source of contradiction on this point, as Russell himself describes his career history in his 2008 oral history:

At some time around, I think it was 1961, late 1961, early 1962, I had gotten bored with working on Lisp and got a job at Harvard. And part of that involved my not having a deferment anymore, so I went into the Army Reserve. […] I had to go off for six months of active duty; I came back, management had changed; new management was not nice, and […] about the time I was convinced that I didn’t want to continue working for Harvard, John was moving to California, to Stanford, and offered me a job at Stanford, which I took. So I ended up at Stanford in the fall of 1962.”

Practically every account of the creation of Spacewar! describes Steve Russell as an MIT student at the time of Spacewar!‘s creation. This claim is so widespread I half expect his tombstone will read “Here lies Steve Russell, noted MIT graduate.” In fact, Steve Russell never attended MIT and never earned a degree from any college. He attended Dartmouth for four years, but failed to graduate because he never got around to writing a senior thesis. In the meantime, he had done some work for MIT professor John McCarthy on the side and secured employment at MIT in 1958 in the newly formed AI Lab. He joined TMRC in 1960 despite not being a student, thus further confusing the historical record, before gaining employment at the Littauer Statistical Laboratory at Harvard by mid 1961 (while Russell is unsure of the sequence of events, he was at Harvard at the same time Graetz was there and Graetz was back at MIT in summer 1961). He stayed there — minus six months of Army Reserve duty — until he departed for Stanford in the Fall of 1962. If you take nothing else away from this blog post, please, please come away with the knowledge that Steve Russell never attended MIT and was no longer even an employee of the university at the time he took the lead on creating Spacewar!

Anyway, the McKenzie deposition appeared to fix the rest of the Spacewar! timeline, and indeed these were the last new chronological revelations that I incorporated into my book. Alas, history is a frustratingly fluid discipline despite being stuck in the past, and Ethan Johnson made an additional discovery after I had locked my manuscript. It turns out the MIT student newspaper, The Tech, is available in its entirety online, and it eagerly announced the impending public unveiling of Spacewar! in the April 25, 1962 issue:

For Parents’ Weekend the PDP1 will run [Spacewar!] for parents and their Techmen between 12 p.m. and 6 p.m., with a special version designed for this purpose. As an example of the whimsical uses of computers this is something parents shouldn’t miss. As a simplistic preview of future war games, it might well be classified were this report to fall into the wrong hands.

At first glance, this does not seem to change anything. In fact, it further confirms that Spacewar! made its debut at that famous May open house that keeps coming up. However, if we delve further into the same issue, we learn that Parents’ Weekend is coming up on Saturday and Sunday. April 25 was a Wednesday, so Parents’ Weekend is actually April 28-29!

This may seem like a minor shift in the timeline, but it has important implications. The surviving version of Graetz’s hyperspace patch is dated May 2, 1962, three days after the Parents’ Weekend concluded. This strongly implies hyperspace may not have been available at the public unveiling. The May 2 revision is not the first implementation of this code if the version number is any guide, so it is possible an earlier version of the patch found its way into the game. This is unlikely, however, because a full description of how Spacewar! works is included in the April 25 article and hyperspace is not mentioned at all. Was it patched in over the next few days? Possibly, but I am inclined to believe it just missed the public unveiling. Alas, my book will need to be corrected.

So now that we have explored all the sources, here is the Spacewar! timeline as best as it can be figured at present:

Summer 1961: Members of the hacker community at MIT, which includes new university employee Martin Graetz, learn that DEC is about to donate a PDP-1 computer to the university. Graetz wants to create a new demonstration program for the machine and enlists his roommates, Harvard employees Wayne Wiitanen and Steve Russell, to brainstorm ideas. Sometime before August 10, they decide to create a game featuring spaceships shooting at each other inspired by their love of the Lensman series of novels by E.E. “Doc” Smith.

September 15, 1961: The donated PDP-1 is installed in the RLE.

Fall 1961: Russell, who still comes around to hang out with his TMRC buddies on evenings and weekends despite no longer working at MIT, starts bragging about the cool program he has dreamed up for the PDP-1 display. Everyone gets excited and starts pressuring him to implement it once the display arrives.

December 29, 1961: The display for the PDP-1 is installed.

January 1962: Steve Russell begins coding Spacewar!, and before the end of the month he has created the first motion object for the game “a dot which could accelerate and change direction under switch control.”

February 1962: Work continues until by the end of the month a barebones version of the game exists consisting of “just the two ships, a supply of fuel, and a store of ‘torpedoes’ — points of light fired from the nose of the ship. Once launched, a torpedo was a ballistic missile, zooming along until it either hit something (more precisely, until it got within a minimum distance of a ship or another torpedo) or its ‘time fuse’ caused it to self-destruct.”

Early March 1962: AI Labs programmer Dan Edwards, who was instrumental in helping Russell get the ships up on the screen, takes it upon himself to add gravity to the game to make it more strategic after Russell pleads lack of skill to make the addition himself.

March 13, 1962: Peter Samson’s “Expensive Planetarium” is patched into the game, providing a scrolling starfield that accurately depicts the actual position and relative brightness of the stars visible from North America [Note: As there is no exact date tied to the gravity addition, its possible that Samson’s contribution came before gravity. I have placed them in this order because Brand’s Rolling Stone article did so. Being written in 1972, it is the earliest source on the matter, meaning memories were presumably freshest.

March 19, 1962: Bob Saunders installs control boxes of his own design on the PDP-1 to make playing Spacewar! less arduous.

March 25, 1962: Spacewar! exists in a largely completed form by this date in a version designated 2B. Ships, torpedoes, gravity, and starfield are all present and operational.

April 2, 1962: Version 2B is slightly modified. Gameplay remains unchanged.

April 28-29, 1962: Spacewar! is played in a public setting for the first time during the annual MIT Parents’ Weekend.

May 2, 1962: Martin Graetz completes a patch adding a hyperspace feature to the game.

They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies That Shaped the Video Game Industry, Vol. I 1971-1982 is available in print or electronically direct from the publisher, CRC Press, as well as through Amazon and other major online retailers.

Just to note my stance on the last point before the timeline, I am inclined to believe that Hyperspace was not implemented at the initial showing in April. Development is certainly a fluid thing and it’s not remotely inconceivable that I’m wrong and it was present, this is a matter of comparing later accounts of Spacewar! to the ones that date around the time of the exhibition.

Almost every single look at Spacewar will mention hyperspace so its omission gets me suspicious. On top of that, The Tech issue mentions specifically that torpedos were affected by gravity because players didn’t like when they ignored the gravitational pull. It’s my suspicion that the implementation of hyperspace overrode that concern, as players subsequently had more options with which to avoid a missile shuttling past the usual flow of the ships.

McKenzie also describes how hyperspace was actually achieved from his recollections, “[W]hen you are using the control switches, the test word switches on the first console, if you simultaneously turn on the counterclockwise and the clockwise rotation switches, you’re immediately thrown into, quote, hyperspace.” This to me says that our assumption that the original controllers (the controllers he would have remembered) were built with a hyperspace function via one of the levers is anachronistic.

The only other contemporaneous report of Spacewar is the issue of DECUSCOPE from April 1962 which fails to mention hyperspace despite giving a thorough rundown on the other features of the game. This viewing could have been anytime before May when the issue shipped though makes the most sense if notified by the Parent’s Day or the article in The Tech. Again it’s not necessarily the case, just pieces that imply something missing.

I know absence of evidence is not evidence of absence and hyperspace was clearly *intended* as early as April 2nd but I think this development moment was very important in terms of this seminal game’s development that shouldn’t be lost if it’s true. Spacewar was one of the first games that was really ‘designed’ and I think every variation of it is important even if it doesn’t really matter who first saw it at the end of April 1962.

Regarding hyperspace:

Please mind that the version from 2 May 1962 bears the rather astronomical version number “VIci”, which was certainly not the very first version. Moreover, the auto-restart patch required by Spacewar! 2B patches not into the game itself, but rather into the hyperspace patch. So the hyperspace patch is quite a requirement for a tournament-like game, probably from quite early on. (The code of the patch also shows some signs of being repeatedly extended and modified, while being confined to a previously assigned space.)

Regarding the controllers and hyperspace:

Mind that activating the turn controls (and releasing them at once, which actually triggers hyperspace in Spacewar! 2B) was perfectly based with the very first controllers, which were built from a quadruple push-button block as used by office phones.

Compare:

https://www.masswerk.at/spacewar/inside/insidespacewar-pt5-ships.html#first_controlboxes

Also, many thanks for the mention! 🙂

Correction: “was perfectly based with the very first controllers” was meant to be, “was perfectly possible with the very first controllers”

Something I forget to mention: We have the wiring diagram for the control boxes, where the hyperspace position of the thrust/hyperspace lever shortens the turn controls at once (see the previous link, just above the linked section) and the DECUS paper “Spacewar! Real-Time Capability of the PDP-1” by J.M. Graetz (held in summer 1962, see https://www.masswerk.at/spacewar/decus1962/) provides the description:

“Hyperspace is entered by pushing the blast lever forward and releasing.”

Mind, “and releasing”, which applies to Spacewar! 2B, while in later versions hyperspace is triggered by the activation of both turn controls. This is actually of interest, since it would have been easy to accidentally activate both turn controls at once with switches or button-type controllers, but releasing them at once is quite a distinct action. However, this is not an issue with a single clockwise/counterclockwise turn lever as seen on the control boxes, we all know. This is also a strong indication for hyperspace predating the lever-type control boxes.